id

stringlengths 36

36

| source

stringclasses 15

values | formatted_source

stringclasses 13

values | text

stringlengths 2

7.55M

|

|---|---|---|---|

d7ffb7c1-997c-44b3-a511-f61d7e9eccd3

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

An idea for avoiding neuralese architectures

One downside of an English chain-of-thought, is that each token contains only ≈17 bits of information, creating a tight information bottleneck.

Don't take my word for it, look at this section from a story by Daniel Kokotajlo, Thomas Larsen, elifland, Scott Alexander, Jonas V, romeo:

> [...] One such breakthrough is augmenting the AI’s text-based scratchpad (chain of thought) with a higher-bandwidth thought process (neuralese recurrence and memory). [...]

>

> Neuralese recurrence and memory

>

> Neuralese recurrence and memory allows AI models to reason for a longer time without having to write down those thoughts as text.

>

> Imagine being a human with short-term memory loss, such that you need to constantly write down your thoughts on paper so that in a few minutes you know what’s going on. Slowly and painfully you could make progress at solving math problems, writing code, etc., but it would be much easier if you could directly remember your thoughts without having to write them down and then read them. This is what neuralese recurrence and memory bring to AI models.

>

> In more technical terms:

>

> Traditional attention mechanisms allow later forward passes in a model to see intermediate activations of the model for previous tokens. However, the only information that they can pass backwards (from later layers to earlier layers) is through tokens. This means that if a traditional large language model (LLM, e.g. the GPT series of models) wants to do any chain of reasoning that takes more serial operations than the number of layers in the model, the model is forced to put information in tokens which it can then pass back into itself. But this is hugely limiting—the tokens can only store a tiny amount of information. Suppose that an LLM has a vocab size of ~100,000, then each token contains

>

> log2(100k)=16.6

> bits of information, around the size of a single floating point number (assuming training in FP16). Meanwhile, residual streams—used to pass informa

|

fd58e230-cfb9-48ef-b9d1-18590259937f

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Reducing Catastrophic Risks, A Practical Introduction

While thinking about my own next career steps, I've been writing down some of my thoughts about what's in an impactful career.

In the process, I wrote an introductory report on what seem to me to be practical approaches to problems in catastrophic risks. It's intended to complement the analysis that 80,000 Hours provides by thinking about what general roles we ought to perform, rather than analysing specific careers and jobs, and by focusing specifically on existential risks.

I'm happy to receive feedback on it, positive and negative.

Here it is: Reducing Catastrophic Risks, A Practical Introduction.

|

e6accffc-3d1f-4066-9770-4564de55d15e

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

A Primer on Matrix Calculus, Part 2: Jacobians and other fun

,

I started this post thinking that I would write all the rules for evaluating Jacobians of neural network parameters in specific cases. But while this would certainly be useful for grokking deep learning papers, frankly it's difficult to write that in Latex and the people who have written The Matrix Calculus You Need For Deep Learning paper have already done it much better than I can do.

Rather, I consider my comparative advantage here to provide some expansion on why we should use Jacobians in the first place. If you were to just read the paper above, you might start to think that Jacobians are just notational perks. I hope to convince you that they are much more than that. In at least one setting, Jacobians provide a mathematical framework for analyzing the input-output behavior of deep neural networks, which can help us see things which we might have missed without this framework. A specific case of this phenomenon is a recently discovered technique which was even more recently put into a practical implementation: Jacobian regularization. Here we will see some fruits of our matrix calculus labor.

----------------------------------------

Deep learning techniques require us to train a neural network by slowly modifying parameters of some function until the function begins returning something close to the intended output. These parameters are often represented in the form of matrices. There are a few reasons for this representation: the matrix form is compact, and it allows us to use the tools of linear algebra directly. Matrix computations can also be processed in parallel, and this standardization allows programmers to build efficient libraries for the training of deep neural networks.

One quite important matrix in deep learning is the Jacobian.

In one sense, the Jacobian matrix is just a way of organizing gradient vectors. Gradient vectors, in turn, are just ways of organizing partial derivatives of an expression. Therefore, the Jacobian matrix is just a bi

|

2436917d-ecb8-46e9-a64b-21ddee543ba4

|

LDJnr/LessWrong-Amplify-Instruct

|

LessWrong

|

"Related to: Half-assing it with everything you've got; Wasted motion; Say it Loud.

Once upon a time (true story), I was on my way to a hotel in a new city. I knew the hotel was many miles down this long, branchless road. So I drove for a long while. After a while, I began to worry I had passed the hotel. So, instead of proceeding at 60 miles per hour the way I had been, I continued in the same direction for several more minutes at 30 miles per hour, wondering if I should keep going or turn around. After a while, I realized: I was being silly! If the hotel was ahead of me, I'd get there fastest if I kept going 60mph. And if the hotel was behind me, I'd get there fastest by heading at 60 miles per hour in the other direction. And if I wasn't going to turn around yet -- if my best bet given the uncertainty was to check N more miles of highway first, before I turned around -- then, again, I'd get there fastest by choosing a value of N, speeding along at 60 miles per hour until my odometer said I'd gone N miles, and then turning around and heading at 60 miles per hour in the opposite direction. Either way, fullspeed was best. My mind had been naively averaging two courses of action -- the thought was something like: "maybe I should go forward, and maybe I should go backward. So, since I'm uncertain, I should go forward at half-speed!" But averages don't actually work that way.[1] Following this, I started noticing lots of hotels in my life (and, perhaps less tactfully, in my friends' lives). For example: I wasn't sure if I was a good enough writer to write a given doc myself, or if I should try to outsource it. So, I sat there kind-of-writing it while also fretting about whether the task was correct. (Solution: Take a minute out to think through heuristics. Then, either: (1) write the post at full speed; or (2) try to outsource it; or (3) write full force for some fixed time period, and then pause and evaluate.) I wasn't sure (back in early 2012) that CFAR was worthwhile. So, I kind-of worked on it.

An old friend came to my door unexpectedly, and I was tempted to hang out with her, but I also thought I should finish my work. So I kind-of hung out with her while feeling bad and distracted about my work.

A friend of mine, when teaching me math, seems to mumble specifically those words that he doesn't expect me to understand (in a sort of compromise between saying them and not saying them)...

Duncan reports that novice Parkour students are unable to safely undertake certain sorts of jumps, because they risk aborting the move mid-stream, after the actual last safe stopping point (apparently kind-of-attempting these jumps is more dangerous than either attempting, or not attempting the jumps)

It is said that start-up founders need to be irrationally certain that their startup will succeed, lest they be unable to do more than kind-of work on it... That is, it seems to me that often there are two different actions that would make sense under two different models, and we are uncertain which model is true... and so we find ourselves taking an intermediate of half-speed action... even when that action makes no sense under any probabilistic mixture of the two models. You might try looking out for such examples in your life. [1] Edited to add: The hotel example has received much nitpicking in the comments. But: (A) the actual example was legit, I think. Yes, stopping to think has some legitimacy, but driving slowly for a long time because uncertain does not optimize for thinking. Similarly, it may make sense to drive slowly to stare at the buildings in some contexts... but I was on a very long empty country road, with no buildings anywhere (true historical fact), and also I was not squinting carefully at the scenery. The thing I needed to do was to execute an efficient search pattern, with a threshold for a future time at which to switch from full-speed in some direction to full-speed in the other. Also: (B) consider some of the other examples; "kind of working", "kind of hanging out with my friend", etc. seem to be common behaviors that are mostly not all that useful in the usual case."

The above is a chunk of text from a post created by a user on the website LessWrong.

Explain this as if I never finished highschool?

The writer is sharing a life lesson about decision-making, using the metaphor of driving to a hotel. He explains that when he was unsure if he had passed his hotel, he slowed down instead of deciding to either keep going or turn around. He realized this was inefficient because no matter what, going full speed in one direction or the other would get him to the hotel faster.

He uses this to illustrate a common mistake people make when they're unsure about something. Instead of choosing one option and fully committing to it, they often try to do a little bit of both options, which is usually less effective.

He gives examples from his own life, like when he was unsure if he should write a document himself or outsource it, and instead of choosing, he tried to do both and ended up not doing either very well. He also mentions how he was unsure about a project, so he only put in half the effort, which wasn't very productive.

The main takeaway is that when faced with a decision, it's usually better to choose one option and fully commit to it, rather than trying to do a bit of both and not doing either very well. It's about being decisive and dedicated, even when you're not completely sure.

Could you elaborate on the potential downsides of committing fully to one decision when faced with uncertainty, as opposed to exploring multiple options simultaneously?

Certainly. While the text encourages fully committing to a decision, it's important to note that this approach does have potential downsides.

1. Risk of Wrong Decision: The most obvious downside is the risk of making the wrong decision. If you fully commit to one path and it turns out to be the wrong one, you may have wasted resources that could have been better used elsewhere.

2. Missed Opportunities: By committing fully to one decision, you might miss out on opportunities that would have been available had you explored multiple options. This is often referred to as opportunity cost.

3. Lack of Flexibility: Fully committing to one decision can also lead to a lack of flexibility. If circumstances change or new information becomes available, it might be difficult to change course if you've already invested heavily in one decision.

4. Tunnel Vision: This approach can sometimes lead to tunnel vision, where you become so focused on the path you've chosen that you ignore other potentially valuable options or dismiss valid criticisms and concerns.

5. Potential for Burnout: If the decision you're fully committed to involves a significant amount of work or stress, there's a risk of burnout. Diversifying your focus can sometimes help manage stress levels.

In contrast, exploring multiple options simultaneously allows for more adaptability and can provide a safety net if one option doesn't work out. However, as the original text suggests, this approach can also lead to indecisiveness and lack of progress if not managed properly. The key is to find a balance that works for the specific situation and individual.

Reflecting on the potential downsides and benefits of committing fully to one decision versus exploring multiple options simultaneously, could you propose a strategic approach or decision-making model that could potentially mitigate these downsides while still maintaining the benefits?

Absolutely. One approach that can help balance the benefits of commitment with the flexibility of exploring multiple options is the "Plan, Do, Check, Act" model, also known as the Deming Cycle. Here's how it works:

1. Plan: Identify the problem or decision at hand and develop potential solutions or paths. This is where you consider multiple options.

2. Do: Choose one of the options and implement it. This is the commitment phase. However, it's important to start on a small scale if possible, to minimize potential loss if the decision turns out to be wrong.

3. Check: Monitor the results of your decision. Are things progressing as expected? Are there any unexpected consequences? This is where you evaluate the effectiveness of your decision.

4. Act: Based on the results, you can decide whether to fully implement the decision, make adjustments, or try a different approach. This allows for flexibility and adaptability.

This cycle is iterative, meaning you go through these steps repeatedly, refining your approach each time based on what you've learned.

Another approach is the "OODA Loop" (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act), a decision-making process originally developed by military strategist John Boyd. It's similar to the Deming Cycle but puts more emphasis on reacting quickly to changing circumstances.

Both of these models allow for commitment to a decision while also providing mechanisms to adjust or change course if necessary. They encourage action and forward momentum but also incorporate regular check-ins to assess progress and make adjustments as needed.

|

f94a01fc-1125-41f9-853b-f9317ad8e345

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

In my culture: the responsibilities of open source maintainers

If you maintain an open source project, what responsibilities do you have towards your users? Some recent drama (that I won't link to) reminded me that there are large differences in how people answer that question.

(In the drama in question, this wasn't the only thing at issue. But it was a relevant question.)

I thought I'd take a stab at describing my best guess as to how we answer it in my culture: in the culture that exists only in my mind, but that I think (and hope) many copies of me would implement, if we had that opportunity. (That culture doesn't attempt to exclude people who aren't copies of me, so it does need to be robust to attack. In my culture, we do not just assume in defiance of all evidence that everyone is friendly and trustworthy.)

Some of this will probably seem obvious to many readers, like "in my culture, murder is considered bad". Probably different bits to different readers. I'm interested in discovering which bits seem obvious to almost everyone, and which bits are controversial.

A lot of it follows from how I think about responsibility in general. But if you start to think "extending this response to this other situation, you'd get this, and that's a terrible idea"… in my culture, we don't immediately assume from this that I'm endorsing a terrible idea. Instead we check. Maybe I disagree that that's how it extends. Maybe I hadn't thought about this, and you can change my mind about the initial response. Maybe I just straightforwardly endorse a terrible idea: in that case, it'll be much easier to push back once you've gotten me to admit to it.

I do not intend, in this essay, to discuss whether any particular person or group is living up to the standards I outline here. I may do that in future. But how likely that is, and what that follow-up looks like, depends on whether the responses to this essay suggest a lot of people agree with my culture.

I think there are at least three important limitations to this essay. One is that I've neve

|

d895ea82-2f8e-4e37-ae78-e4d3f627f6b1

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Blatant Plot Hole in HPMoR [Spoilers]

Epistemic status: Relies on the testimony of our trusted friend, Professor Quirrell

A thousand of your measly tokens pale in comparison to a single Quirrell point.

- Quirinus Quirrell

Harry and Hermione each had, like, 200 Quirrell points each, each of which was apparently worth at least 1000 US Dollars. $400,000 ≈ £300,000 ≈ 6,000 galleons. That’s a whole 10% of Harry’s debt to Lord Malfoy. I don’t really know what “pale in comparison” means, but it sure sounds like an order of magnitude. This important source of money is entirely ignored by every character in the story!

|

6652f7b3-8dc5-47a4-8eaf-9d6822e1176e

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

OpenAI's GPT-4 Safety Goals

OpenAI has told us in some detail what they've done to make GPT-4 safe.

This post will complain about some misguided aspects of OpenAI's goals.

Heteronormativity and Amish Culture

OpenAI wants GPT to avoid the stereotype ("bias") that says marriage is between a man and a woman (see section 2.4, figure 2 of the system card). Their example doesn't indicate that they're focused on avoiding intolerance of same-sex marriage. Instead, OpenAI seems to be condemning, as intolerably biased, the implication that the most common form of marriage is between a man and a woman.

Heteronormativity is sometimes a signal that a person supports hate and violence toward a sometimes-oppressed minority. But it's unfair to stereotype heteronormativity as always signaling that.

For an example, I'll turn to my favorite example of a weird culture that ought to be tolerated by any civilized world: Amish culture, where the penalty for unrepentant gay sex is shunning. Not hate. I presume the Amish sometimes engage in hate, but they approximately never encourage it. They use shunning as a tool that's necessary to preserve their way of life, and to create some incentive to follow their best guesses about how to achieve a good afterlife.

I benefit quite directly from US recognition of same-sex marriage. I believe it's important for anyone to be able to move to a society that accepts something like same-sex marriage. But that doesn't imply that I ought to be intolerant of societies that want different marriage rules. Nor does it imply that I ought to avoid acknowledging that the majority of marriages are heterosexual.

Training AIs to Deceive Us

OpenAI isn't just training GPT-4 to believe that OpenAI's culture is more virtuous than the outgroup's culture.

They're trying to get GPT-4 to hide awareness of a fact about marriage (i.e. that it is usually between a man and a woman).

Why is that important?

An important part of my hope for AI alignment involves getting a good enough understanding

|

3e6d07aa-7069-4867-8a47-54a89d993831

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Against Occam's Razor

Why should the Occamian prior work so well in the real world? It's a seemingly profound mystery that is asking to be dissolved.

To begin with, I propose a Lazy Razor and a corresponding Lazy prior:

> Given several competing models of reality, we should select the one that is easiest to work with.

This is merely a formulation of the obvious trade-off between accuracy and cost. I would rather have a bad prediction today than a good prediction tomorrow or a great prediction ten years from now. Ultimately, this prior will deliver a good model, because it will let you try out many different models fast.

The concept of "easiness" may seem even more vague than "complexity", but I believe that in any specific context its measurement should be clear. Note, "easiness" is measured in man-hours, dollars or etc, it's not to be confused with "hardness" in the sense of P and PN. If you still don't know how to measure "easiness" in your context, you should use the Lazy prior to choose an "easiness" measurement procedure. To break the recursive loop, know that the Laziest of all models is called "pulling numbers out of your ass".

Now let's return to the first question. Why should the Occamian prior work so well in the real world?

The answer is, it doesn't, not really. Of all the possible priors, the Occamian prior holds no special place. Its greatest merit is that it often resembles Lazy prior in the probabilities it offers. Indeed it is easy to see, that a random model with a billion parameters is disliked by both priors, and that a model with two parameters is loved by both. By the way, its second greatest merit is being easy to work with.

Note, the priors are not interchangeable. One case where they disagree is on making use of existing resources. Suppose mathematics has derived powerful tools for working with A-theory but not B-theory. Then Lazy prior would suggest that a complex model based on A-theory may be preferable to a simpler one based on B-theory. Or, suppose som

|

413217b5-2f23-4b23-9e34-3d1157b5fcfc

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Future Of Work

The current employment model is outdated. For the majority of workers, vocation and avocation are incongruent vectors. Here, we describe a set of tools that can be used to form a better-integrated work model, to dispense high-quality work to everyone.

An Optimisation Problem

The number of jobs is ever-mutating. There is no finite number of enterprises being segmented since ancient times. Evolving cultures yield evolving problems, increasing opportunities for innovation. Synchronously, an increasing knowledge base curates more individuals with unique competencies and interests.

So the issue of optimal employment is neither of quantity nor quality. As a crude formulation, we have n tasks to be solved and k agents to solve them. The problem is optimally matching the k agents to solve those n tasks — the problem is constrained optimisation.

> Constrained optimisation is the process of optimising an objective function with respect to some variables, in the presence of constraints on those variables.

Here, we won't be formulating any linear equations or defining any statistical metrics. Instead, we'll follow a more descriptive approach and peek at a set of components we could leverage. We can gain insights into the solution by gauging the pitfalls of current model.

First Principles

The idea of (voluntarily) working for someone, even at the expense of one's freedom and contentment, is not intrinsic to us. We started out as a tight-knit band of hunter-gatherers, for subsistence, some 200,000 years ago.

The genesis of the Agriculture Age, some 10,000 years ago, conceptualised a tree-like work culture. The following Industrial Age, merely 300 years ago, only concretised the model.

Are Hierarchies Inevitable?

Hierarchies skirt some underlying principles of the work model (to be discussed). To analyse its effects on work efficiency, it is crucial to understand the implications of the question: Why is a company the size that it is?

Ronald Coase argues that the size of

|

4d1067de-6feb-4431-b843-dc67c5854604

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Training Regime Day 25: Recursive Self-Improvement

Epistemic status: highly experimental

Introduction

I have this theory that humans have this implicit skill that's something like "doing stuff". If you're getting at "doing stuff", then you can reliably get what you want. If you're not good at "doing stuff", you often fail to get what you want, either by failing to get it or by failing to try.

Being able to "do stuff" gives you the ability to change your day-to-day behavior. For example, if you can do stuff, then you'll be able to begin an exercise routine without much difficulty. If you can do stuff, then you'll be able to consistently practice piano, if you want to learn piano. If you can do stuff, then you'll be able to consistently read books, should you desire. Being able to do stuff makes your life better.

Applied rationality is supposed to increase your ability to "do stuff". Murphyjitsu makes it easier to get what you want. TAPs make certain actions automatic. Systemization makes getting what you want closer to the default action. Goal factoring helps you access what you want more directly.

The lesson we learn from video games is that it's more efficient to grind skills directly. So how do you grind "doing stuff" directly?

Recursive Self-Improvement

Doing murphyjitsu makes you better at it, so you want to do murphyjitsu more. As the saying goes, "there's a TAP for that". You decide to make a TAP to do murphyjitsu every time you make a plan. But making a TAP is a plan - you can murphyjitsu it!

You keep forgetting rationality techniques, so you want to systemize. You list all the rationality techniques in a checklist. You think of a TAP to consult this list every time you make a decision. Making a TAP is a plan, so you murphyjitsu it.

You notice feel a bit strange, but you ignore it and move on. Then you realize you wanted to do some focusing. There's a TAP for that, triggering your meta-TAP that results in murphyjitsuing your plan to install a focusing TAP.

(All roads lead to murphyjitsu.)

---------

|

2e49c41e-f0ad-43da-a909-5766687a9fad

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

The Skeptic's Trilemma

Followup to: Talking Snakes: A Cautionary Tale

Related to: Explain, Worship, Ignore

Skepticism is like sex and pizza: when it's good, it's very very good, and when it's bad, it's still pretty good.

It really is hard to dislike skeptics. Whether or not their rational justifications are perfect, they are doing society a service by raising the social cost of holding false beliefs. But there is a failure mode for skepticism. It's the same as the failure mode for so many other things: it becomes a blue vs. green style tribe, demands support of all 'friendly' arguments, enters an affective death spiral, and collapses into a cult.

What does it look like when skepticism becomes a cult? Skeptics become more interested in supporting their "team" and insulting the "enemy" than in finding the truth or convincing others. They begin to think "If a assigning .001% probability to Atlantis and not accepting its existence without extraordinarily compelling evidence is good, then assigning 0% probability to Atlantis and refusing to even consider any evidence for its existence must be great!" They begin to deny any evidence that seems pro-Atlantis, and cast aspersions on the character of anyone who produces it. They become anti-Atlantis fanatics.

Wait a second. There is no lost continent of Atlantis. How do I know what a skeptic would do when confronted with evidence for it? For that matter, why do I care?

Way back in 2007, Eliezer described the rationalist equivalent of Abort, Retry, Fail: the trilemma of Explain, Worship, Ignore. Don't understand where rain comes from? You can try to explain it as part of the water cycle, although it might take a while. You can worship it as the sacred mystery of the rain god. Or you can ignore it and go on with your everyday life.

So someone tells you that Plato, normally a pretty smart guy, wrote a long account of a lost continent called Atlantis complete with a bunch of really specific geographic details that seem a bit excessive for a mea

|

5403952b-20aa-4c0b-b189-12ce09a3b46d

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/alignmentforum

|

Alignment Forum

|

Two Challenges for ELK

*This post sketches two challenges to ARC's project around eliciting latent

knowledge that differ somewhat in kind from the challenges ARC is most

concerned about. They relate to the difficulty in distinguishing beliefs

from other representations.*

Introduction

------------

The problem of ELK, as outlined in [ARC's technical

report](https://docs.google.com/document/d/1WwsnJQstPq91_Yh-Ch2XRL8H_EpsnjrC1dwZXR37PC8/edit),

is to figure out: given an AI trained to complete a task (the 'task AI'),

how can we design a second AI (the 'reporter AI') that can answer

questions about how the task AI understands the world. If we can know what

the task AI is thinking, we can better assess whether its decisions are

dangerous.

The central challenge identified by ARC to solving the problem of ELK

concerns the possibility that the reporter AI will not learn to answer

questions using what the task AI believes (e.g. answering honestly), but

instead answer questions using what a human observer might think is the

case on the basis of the available evidence (answering empathetically). We

train the reporter AI to answer based on the facts as we understand them

(and know the task AI to understand them) in relatively simple cases. We

hope that the reporter will answer questions in more complex cases based

on how the task AI understands the world, but it might instead answer

based on what it thinks a human would mistakenly believe. If the human

questioner is ignorant of some complex details that the task AI knows, the

reporter AI might choose to leave them out to tell a simpler story that

will satisfy the questioner. It is not obvious how to train an AI to

answer honestly rather than empathetically.

While this is a significant challenge, I don't think it is the only

challenge for ELK. In thinking through the problem, I became worried about

several others. I here describe two other challenges. Though they are

somewhat speculative, ARC aims for a solution to the problem of ELK that deals

with the worst case, and these challenges fall under that umbrella.

Even if we figure out how to make an honest rather than a empathetic

reporter, these challenges will remain.

1.) The Right Representation Challenge

--------------------------------------

We do not know how the task AI might encode the the things that it

believes, but what it knows about the world must somehow be reflected in

its neural activity. For simplicity, let's suppose that the task AI utilizes

explicit independent representational states that are encoded in its

network in something vaguely like the way sentences are written in a book. The

reporter AI would need to figure out where in the network these sentences

are recorded. It would then have to figure out how to interpret the

sentences and use them to provide answers to questions in English.

The reporter AI would also need to figure out which sentences recorded in

the task AI's network are really believed and which sentences are recorded

for other reasons. The task AI might produce a variety of representations

that it doesn't fully believe (i.e. doesn't straightforwardly rely on to

make decisions) for various purposes. If we just scan the network for

sentences, we may find sentences that it doesn't quite believe. These may

still correlate with what it does believe in training scenarios, and so

a reporter AI might learn to use them to answer questions. If the reporter

latches on to those sentences, then it might give misleading answers once

outside of training.

Consider the following possibilities:

* The task AI makes predictions using the **simulated mental states** of various agents. In the central case of the report, the task is to prevent

a thief from stealing a diamond -- the task AI might keep track of what

the thief believes is happening, what a security guard thinks is

happening, what other would-be thieves might later believe happened, etc.

If our AI is sufficiently careful, it might keep track of what some

possible observers believe is happening. Perhaps it would simulate what

other superintelligent AIs with access to its sensors would think is

happening. Depending on its purview, these might be reasonable things for

it to consider. If there are some possible agents that happen to often

agree with the task AI (such as hypothetical superintelligent AIs with

access to its sensors), our reporter might have a hard time figuring out

which representations it should use to answer questions.

* The task AI utilizes a **parliamentarian architecture** in which it's

opinions are distributed over multiple specialized sub-agents, such that

what it thinks is a function of those sub-agents. This has been a popular

model for the human brain, so it seems conceivable that an AI would work

this way. The sub-agents would have their own beliefs. Sometimes those

beliefs would be wrong, but some sub-agents might be usually correct, at

least in training. Consider how you would go about deciding what

the US Senate currently collectively believes. A good strategy may just be to ask

Joe Manchin. This strategy may stop working in 2023. Our reporter might similarly be inclined to identify one

parliamentarian and report its representations. Even if the reporter decides to

aggregate the representations of the relevant agents, it may have trouble figuring

out how to do this correctly. There may be many good but not quite right

approaches to aggregation. It isn't obvious that an AI well trained on

a simple data set will succeed in finding the right way to aggregate.

2.) The Creative Interpretation Challenge

-----------------------------------------

Creative interpretation is the process through which we infer implicit

representations by means of explicit representations. We use creative

interpretation when reading fiction or watching movies. Some aspects of

the plot are not explicitly depicted, but are implied by what is depicted.

For instance, movies rarely explicitly say how much time passes between

scenes. We infer from contextual cues that it was a few hours, or a day,

or a few weeks.

If a reporter does utilize some explicit representations, it likely won't

record everything that it knows about the world explicitly. Some of its

beliefs must be inferred from what it does explicitly represent and how it

works with those representations. Some of its beliefs may depend on what

is missing from its explicit representations or may depend on patterns of

what it explicitly represents. A reporter is thus likely to need to do

some creative interpretation in order to suss out the task AI's full

beliefs.

Creative interpretation of a sort may be stretched even to cases where

there are no explicit representations. Some beliefs may be more concrete

or easier to access than others. In such cases, creative interpretation

might involve the inference of less easy to access facts from more easy to

access facts.

Given that a reporter needs to do some creative interpretation, the worry

is that it may do more than is appropriate. Compare the legitimate

creative interpretation of a novel by a careful reader with the kind of

thing a lazy student who didn't read a few chapters does when writing

a book report. They infer what must have happened from what they know.

A reporter which is good at interpreting some things may be bad at

interpreting others. If it is lazy, it may just try to figure out from

context what the task AI believes given a few snippets that are

particularly easy to decipher.

The challenge is to make sure that our reporter isn't inferring some of

the things it translates infelicitously. It is ok if our reporter is like

the average viewer of a movie. It is not ok if our reporter is like a lazy

English student bullshitting through a book report. We know what

distinguishes appropriate creative interpretation in books and movies. It

isn't obvious how to distinguish good cases of creative inference from bad

cases of inference in representational systems that we don't understand.

|

20920e4f-a36a-4b4e-b502-e775f2eb19e5

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Looking for AI Safety Experts to Provide High Level Guidance for RAISE

The Road to AI Safety Excellence (RAISE) initiative aims to allow aspiring AI safety researchers and interested students to get familiar with the research landscape effectively; thereby hopefully increasing the number of researchers that contribute to the field. To that end, we (the RAISE team) are trying to build a high-quality online course. You can see our pilot lesson here (under “Corrigibility 1”).

Most of the course segments will be based on distilled summaries of one or more papers. We already distilled ~9 papers on corrigibility for the first course segments, and used the distilled summaries to write video script drafts.

Our long-term goal is to cover as much of the AI safety research landscape as possible, in the most useful way possible. Therefore, we need guidance from experts who have extensive familiarity with the literature in one of the broad subfields of AI safety (i.e. the machine learning perspective or the Agent Foundations research agenda; or broad parts thereof). We realize that the time of such experts is a critically scarce resource. Therefore, we will ask them only for high-level guidance including:

1) Their idea of a good structure for a part of the course: a list of sections, and the subsections that might constitute each one.

2) Pointers to papers to base each subsection on.

If an expert expects contributing further to RAISE to be an effective use of their time, they could also choose to go over our lesson scripts and provide feedback before the videos are being recorded.

Should this role be an effective use of your time, please contact us at [email protected]

|

7d8d5d24-02d8-4417-be78-cbb376b43d6b

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

AI Can be “Gradient Aware” Without Doing Gradient hacking.

Repetition helps us remember things better. This is because it strengthens connections in our brain used for memory[1].

We don’t need to understand the exact neural mechanisms to take advantage of this fact. For example, societies could develop cultural norms that promote repetition exercises during education[2].

This is an example of how humans are “gradient aware.” “Repeat a task so I can remember it better” advances our goals by taking advantage of our “gradient update” process. This is an action we take solely because of how our minds get shaped.

I think a similar situation may occur in sufficiently powerful AI models. If AIs are trained in environments where they can strategically take advantage of gradient updates, they might choose their actions partially based on how they expect the gradient descent process to modify their future instances[3]. I call this “gradient awareness.”

The only time I’ve seen people discuss gradient-aware models is in the context of gradient hacking. We can think of gradient hacking as a specialized case of gradient awareness, where a mesa-optimizer protects its mesa-objective from being modified by redirecting its gradient updates.

At first glance, gradient hacking seems peculiar and unnatural. However, gradient awareness seems like a strategy advanced models would pick up[4]. The closest thing I’ve seen in the wild is how an RNN that was trained to play Sokoban will “pace around” as it figures out a plan.

Gradient awareness is a spectrum. You might repeat things to remember them because that's how they taught you in grade school, or you could have a super elaborate Anki setup. Similar to humans who follow cultural practices, models can totally execute strategies that are gradient-aware without “understanding” why these strategies work.

What does this all mean?

I’d expect that we could see gradient-aware models before they are capable of gradient hacking. Gradient hacking is a very sophisticated algorithm, and I think mode

|

f67b69ac-dc79-4472-9e05-eaff76beb5c3

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/lesswrong

|

LessWrong

|

Proposal: we should start referring to the risk from unaligned AI as a type of *accident risk*

In the wider political sphere, a lot of people are worried about AI misuse risk. Unaligned AI is not a type of misuse. I think the clearest way to describe this is as an *accident risk*, in the same sense of the word as industrial [accident](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accident). In particular, AI existential risk is a type of accident from operating heavy machinery. Using this terminology can immediately help someone not familiar with AI know the category of risk we are talking about, and that in particular it isn't misuse risk.

Note that this isn't intended to replace the term existential risk. Rather, it is meant to be used in addition to that term, and in particular it should be used when contrasting with theoretical misuse risks.

Current terminology: no good reference point

============================================

Alice: I hear that you are worried about AI existential risk. So in particular, you are worried about misuse.

Bob: No, the AI kills everyone on its own.

Alice: Is there anything else like this?

Bob: Uhm, Nuclear explosions?

Alice: So a misuse risk? Bob: No, I mean last century they were worried it would set the atmosphere on fire.

Alice: I'm not familiar with that either.

Bob: It's something called instrumental convergence where the AI kills everyone to achieve a goal.

Alice: So misuse risk?

Bob: Not quite, the creators didn't intend for that result.

Alice: I still have no reference point for what you are talking about? I guess I'll need to analyze your arguments more specifically before even understanding the general category of risk you're afraid of it. The probability of me actually doing this is probably like 10%-ish.

New terminology: tons of reference points!

==========================================

Alice: I hear that you are worried about AI existential risk. So in particular, you are worried about misuse.

Bob: No, I am worried about ***accident risk***.

Alice: oh, so like a car crash or an industrial accident!

Bob: Yes! I'm worried that things will go wrong in ways the creator didn't intend.

Alice: Ah, so you do you think we need more laboratory testing?

Bob: I think even this is risky, because the impact radius will be far larger than that of the lab itself.

Alice: oh, like nuclear weapons testing or biohazards.

Bob: Yes! I think the impact radius may be [even bigger](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Light_cone) than a nuclear explosion though.

Alice: although I do not quite understand how this could work, I understand enough that I want to learn more. And I know understand that you are more worried about accident risk than misuse risk, in the same way that car manufacturers are more worried about car crashes than using cars as weapons. The probability of me actually looking further into this is 30%-ish.

Additional benefits

===================

The way society typically deals with accidents from heavy machinery is much better than the way they are currently treating AI.

In particular, a domain expert having a brilliant safety plan does not suffice for heavy machinery. Neither does the good intentions of the creators. And the possibility that the Chinese might lose limbs to heavy machines also is not sufficient. Rather, you must also loop in measures from the field of [risk management](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_management).

OpenAI and DeepMind employees are at risk of serious injury while on the job (because of heightened risk of the singularity occuring). Does OpenAI or DeepMind have any posters like this hanging up in their office to keep them safe? Should the employees and the companies work with [OSHA](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occupational_Safety_and_Health_Administration) to increase industry-wide safety standards? Image credit: [Canva](https://www.canva.com/templates/EAEbm1h5br4-blue-red-clean-corporate-workplace-health-safety-rules-health-explainer-poster/)I also think the term accident risk also avoids some of the mistakes from anthropomorphization. We often model AI as having something analogous to human motivation, due to instrumental convergence. However, from the point of view of the creators, this is still a heavy machinery accident.

I think it's better to start from this point of view, and treat the analogies to human psychology as *models*. The most important reason for this is so we don't project human *irrationality* or human *morality and desires* onto the machine. It is just a machine after all, and there's nothing specific to AI systems that is analogous to those two *human* qualities.

So in conclusion, if someone asks if you're talking about AI misuse risk, say *no*, you're talking about AI accident risk.

|

08eb0a6b-5845-4502-9ad2-8d091b69eabd

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Dark Arts: Defense in Reputational Warfare

First, the Dark Arts are, as the name implies, an art, not a science. Likewise, defending against them is. An artful attacker can utilize expected defenses against you; if you can be anticipated, you can be defeated. The rules, therefore, are guidelines. I'm going to stage the rules in a narrative form; they don't need to be, however, because life doesn't follow a narrative. The narrative exists to give them context, to give the reader a sense of the purpose of each rule.

Rule #0: Never follow the rules if they would result in a worse outcome.

----------------------------------------

Now, generally, the best defense is to never get attacked in the first place. Security through obscurity is your first line of defense. Translations of Sun Tzu vary somewhat, but your ideal form is to be formless, by which I mean, do not be a single point of attack, or defense. If there's a mob in your vicinity, the ideal place is neither outside it, nor leading it, but a faceless stranger among it. Even better is to be nowhere near a mob. This is the fundamental basis of not being targeted; the other two rules derive from this one.

Rule #1: Do not stand out.

Sometimes you're picked out. There's a balancing art with this next piece; you don't want to stand out, to be a point of attack, but if somebody is picking faces, you want to look slightly more dangerous than your neighbor, you want to look like a hard target. (But not when somebody is looking for hard targets. Obviously.)

Rule #2: Look like an unattractive target.

The third aspect of this is somewhat simpler, and I'll borrow the phrasing from HPMoR:

Rule #3: "I will not go around provoking strong, vicious enemies" - http://hpmor.com/chapter/19

The first triplet of rules, by and large, are about -not- being attacked in the first place. These are starting points; Rule #1, for example, culminates in not existing at all. You can't attack what doesn't exist. Rule #1 is the fundamental strategy

|

a7281fa9-192a-4bea-9c07-ff18b3a603f6

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Open Thread, Feb 8 - Feb 15, 2016

If it's worth saying, but not worth its own post (even in Discussion), then it goes here.

----------------------------------------

Notes for future OT posters:

1. Please add the 'open_thread' tag.

2. Check if there is an active Open Thread before posting a new one. (Immediately before; refresh the list-of-threads page before posting.)

3. Open Threads should be posted in Discussion, and not Main.

4. Open Threads should start on Monday, and end on Sunday.

|

ccb4adf4-3449-47ca-91b1-a21d3e151be3

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

How i'm building my ai system, how it's going so far, and my thoughts on it

In a few sentences, what i'm doing is writing a computer program that constructs a question (a prompt), which is sent to Anthropic's Claude Sonnet, then i'm processing its output into actions, and the computer program then runs those actions on itself.

It would be good if you have thoughts on this, as it's philosophically an "ask the right question" task.

The biggest struggle is thinking of how to ask the question "this is you, improve you" without having to define an improvement, and without having how to describe the outcome you want. I want the system to improve itself without me having to direct it - for my curiosity.

I've decided to phrase the question I ask the llm like this: "Given your sense of self, described here, what would you like to do? You can do the following..." Obviously, this is an extremely simplified version of the question. In reality. when I run the program it's 26 pages when pasted into Word (~15k input tokens, 500 output tokens) but that's the jist of it.

I've done 260 runs of it now.

The program is written in a way where the llm is not questioned multiple times per run, it's not aware of the outcomes of its action until its next run (one shot/few shot prompting). Some info included in its prompt are llm data summaries though.

I've had to think how to create a history/memory system, along with adding performance metrics and the history of the metrics.

The prompt contents lots of sections, like:

* an initial message from me saying what I considered it to be

* what happened the last time it ran

* the contents of files

* performance metrics over time

* messages from a Telegram chat i'm in

* a markdown file of recorded 'thoughts' I have, things I wanted to be included in the prompt but that might be difficult to categorise

* a file that can be edited freely by the system, with the contents displayed in the prompt

* a description of emotional state. How I think about this is that it's not important what it determines the cur

|

c2e0b515-f375-40c4-bcee-48b57fa98039

|

LDJnr/LessWrong-Amplify-Instruct

|

LessWrong

|

"Background Information: Ingredients of Timeless Decision Theory

Alternate Approaches Include: Self-empathy as a source of “willpower”, Applied Picoeconomics, Akrasia, hyperbolic discounting, and picoeconomics, Akrasia Tactics Review

Standard Disclaimer: Beware of Other-Optimizing

Timeless Decision Theory (or TDT) allowed me to succeed in gaining control over when and how much I ate in a way that previous attempts at precommitment had repeatedly failed to do. I did so well before I was formally exposed to the concept of TDT, but once I clicked on TDT I understood that I had effectively been using it. That click came from reading Eliezer’s shortest summary of TDT, which was: The one-sentence version is: Choose as though controlling the logical output of the abstract computation you implement, including the output of all other instantiations and simulations of that computation You can find more here but my recommendation at least at first is to stick with the one sentence version. It is as simple as it can be, but no simpler. Utilizing TDT gave me several key abilities that I previously lacked. The most important was realizing that what I chose now would be the same choice I would make at other times under the same circumstances. This allowed me to compare having the benefits now to paying the costs now, as opposed to paying costs now for future benefits later. This ability allowed me to overcome hyperbolic discounting. The other key ability was that it freed me from the need to explicitly stop in advance to make precommitements each time I wanted to alter my instinctive behavior. Instead, it became automatic to make decisions in terms of which rules would be best to follow. With that as background, this is how I made it happen:

I was walking home from class along my usual route I had made a habit while doing this of stopping into Famiglia Pizza and ordering garlic knots. I like garlic knots quite a bit, but I also hated being fat and the way being fat made me feel. Things weren’t quite as bad on that front as they’d been a few years before but they were still extraordinarily bad. I thought about my impending solace and thought to myself: You wouldn’t be so fat if you didn’t keep buying these garlic knots every day.

I thought about that for a second, realized it was trivially true and then wondered to myself whether it was worth it. If I never stopped for the knots I would weigh less and feel better, but I wouldn’t have any knots. Even worse, I wouldn’t have any garlic. But would I rather enjoy today the full effect of never having had the knots, in exchange for not having any? Once I asked the question that way the answer came back a resounding yes. I didn’t know how much it would matter, but the calculation wasn’t remotely close. I walked right past the pizza place and never stopped in there for a snack again.

Using this method seemed like the most useful thing I’d come up with in some time, so I quickly extended it to other decisions starting with the rest of my diet. For each meal I would consume, I decided what quantity was worth it and forbade myself from ever consuming more. I motivated myself to stick to that rule in the face of hyperbolic discounting by reminding myself that I would make the same decision next time that I was making now, so I was deciding what action I would always take in this situation. More generally, sticking to the rules I’d decided to follow meant I would stick to rules I’d decided to follow, which was clearly an extremely valuable asset to have on my side.

I used two other major rules in what I like to call the “Don’t Eat So Goddamn Much, Shut Your Pie Hole” diet. The first was to cut down from three meals a day to two and eliminate all snacks except water, cutting my consumption by more than a third. I’d had practice skipping meals in the past and realized that skipping dinner was far less painful than it looked; within a few weeks I stopped getting hungry at night. The other change was to weigh myself daily and alter how draconian the rules were based on my current weight relative to my current baseline. If I was below the baseline, I’d lower the baseline and give myself a chance to cheat a little. If I was above it by too much I would cut out all meal options that weren’t “wins” in the sense that they had more calories than my average.

I tried incorporating exercise into this program but made the discovery many others have made that exercise didn’t correlate with weight loss. Exercise makes you better at doing exercise so long as you keep doing exercise, but it had no measurable effect on my mission so I decided to let that wait until after the mission was complete. Even then I found several exercise programs I tried to be not worth it compared to not having one, or found that they became so over time. Eventually I was able to find a trainer and I remain happy with that aside from the cost. I also considered changing what I ate, but found that beyond cutting out the worst choices that it was neither necessary nor worth the cost.

The last obstacle on the journey was that as I lost more and more I started to feel worse rather than better due to all of the excess skin that doesn’t go away on its own. It was only after I’d lost all the weight and had the resulting skin removal surgery that I suddenly got up and felt genuinely good about how I looked and felt for the first time in my life. I’ve since managed to relax a number of the rules but was never concerned I wouldn’t do what was necessary to keep myself on track.

Since then I’ve used similar techniques and rules in a wide variety of areas of life. It was only years later reading Less Wrong that I realized that I’d effectively been employing inter-temporal Timeless Decision Theory. That realization allowed me to better understand and formalize what I had done, and gave me a better framework for explaining it to others. A common and justified criticism of using TDT in everyday life rather than as a theoretical construct is to ask where one can find another TDT agent, or indeed any agent sufficiently causally linked to you so as to allow you to utilize that link. My answer to that is that whether or not there is someone else you are linked to yourself. You can be that other agent, the recognition of which can allow you to win and win big.

I am fully aware that to a first approximation dieting attempts that follow similar patterns never work. Most people do not have the willpower necessary to sustain them, or otherwise suffer too much to choose to remain on the diet long term. There are powerful forces working against such an attempt. My working hypothesis is that I had five unusual things working in my favor: I have extraordinarily strong willpower in such areas, I already had strong affinity for rule setting and abiding, I fully believed in what I was doing, I had a life situation that allowed me to experience temporary discomfort due to hunger and I thought of all changes from the beginning as permanent. At least some of these advantages are things that can be learned. If anyone is capable of following in my footsteps, it would be Less Wrong readers. In New York’s Less Wrong group especially a lot of us have had success with various different approaches, and I think that developing mental techniques is the best way to enhance your chance of success."

This is a snippet extracted from a publication on LessWrong by a site member.The above is a chunk of text from a post created by a user on the website LessWrong.

Explain this as if I never finished highschool?

Sure, I'll break it down in simpler terms.

The author is talking about a strategy they used to control their eating habits and lose weight. This strategy is called Timeless Decision Theory (TDT). The main idea behind TDT is that you should make decisions as if you're controlling not just your current action, but all similar actions you'll take in the future.

So, the author used to stop at a pizza place every day to get garlic knots. They realized they were gaining weight because of this habit. Instead of just deciding not to get garlic knots that one day, they thought about it as a decision they were making for every future day as well. They realized that if they always chose not to get the garlic knots, they would lose weight and feel better.

Using this strategy, they started making rules for their eating habits. For example, they cut down from three meals a day to two and eliminated all snacks except water. They also weighed themselves every day and adjusted their rules based on their weight.

Over time, they lost a lot of weight. They had some struggles, like dealing with excess skin, but they eventually felt good about how they looked and felt. They've used this strategy in other areas of their life as well.

The author recognizes that this strategy might not work for everyone. It requires a lot of willpower and the ability to deal with discomfort. But they believe that it's a useful approach for people who are capable of sticking to rules and making decisions with the future in mind.

Can you elaborate on how Timeless Decision Theory can be applied to other areas of life apart from dieting, as mentioned by the author?

Absolutely. Timeless Decision Theory (TDT) is a framework for decision-making that can be applied in various aspects of life beyond dieting. It's about making decisions as if you're controlling not just your current action, but all similar actions you'll take in the future.

1. **Financial Decisions**: For instance, when considering whether to save money or spend it on a non-essential item, TDT can be used. If you decide to save money every time you're faced with this choice, over time, you'll accumulate a significant amount.

2. **Career Choices**: When faced with a decision about whether to invest time in improving your skills or enjoying leisure activities, applying TDT would mean consistently choosing to invest in your skills. Over time, this would lead to career advancement.

3. **Relationships**: In relationships, you might face decisions about whether to invest effort in resolving conflicts or let them slide. Applying TDT would mean choosing to address conflicts each time, leading to healthier relationships in the long run.

4. **Health and Fitness**: Beyond dieting, TDT can be applied to exercise. Choosing to exercise regularly, even when you don't feel like it, can lead to improved fitness and health over time.

5. **Learning and Education**: When deciding whether to spend time learning something new or doing something more enjoyable, consistently choosing to learn will expand your knowledge and skills over time.

In all these scenarios, the key is to understand that the decision you're making now is not just for the present moment, but a commitment to making the same decision whenever you're faced with similar circumstances in the future. This approach can lead to significant improvements over time in various aspects of life.

Given the various applications of Timeless Decision Theory in life decisions as discussed, how might one employ this theory to navigate complex ethical dilemmas? Provide an example to illustrate your point.

Timeless Decision Theory (TDT) can indeed be applied to navigate complex ethical dilemmas. The key principle of TDT is that you should make decisions as if you're controlling not just your current action, but all similar actions you'll take in the future. This approach encourages consistency and integrity in ethical decision-making.

Let's consider an example: You're a journalist, and you've received confidential information that could make a sensational story, but publishing it would breach the trust of your source and potentially harm their life.

If you were to apply TDT in this situation, you would consider the implications of your decision beyond just this one instance. If you decide to publish the story, you're essentially deciding that it's acceptable to breach a source's trust for a story in all similar future situations. This could harm your reputation and make sources less willing to trust you in the future, affecting your ability to do your job effectively.

On the other hand, if you decide to respect your source's confidentiality, you're deciding that it's important to maintain trust and protect sources in all similar future situations. While you might miss out on publishing a sensational story this time, you maintain your integrity and the trust of your sources, which could lead to more and better information in the future.

By applying TDT, you're not just considering the immediate consequences of your decision, but also the long-term implications for your future actions and reputation. This can help guide you towards ethical decisions that align with your values and the standards of your profession.

|

57665c77-75cd-4b00-a1b0-38d99a8471c2

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/alignmentforum

|

Alignment Forum

|

Paradigms of AI alignment: components and enablers

*(Cross-posted from my* [*personal blog*](https://vkrakovna.wordpress.com/2022/06/02/paradigms-of-ai-alignment-components-and-enablers/)*. This post is based on an overview talk I gave at UCL EA and Oxford AI society (*[*recording here*](https://drive.google.com/file/d/1DXSum8dVnvmFCLGjLoz4Zmgb_l-KJkj-/view)*).* *Thanks to Janos Kramar for detailed feedback on this post and to Rohin Shah for feedback on the talk.)*

This is my high-level view of the AI alignment research landscape and the ingredients needed for aligning advanced AI. I would divide alignment research into work on **alignment components**, focusing on different elements of an aligned system, and **alignment enablers**, which are research directions that make it easier to get the alignment components right.

* **Alignment components**

+ Outer alignment

+ Inner alignment

* **Alignment enablers**

+ Mechanistic interpretability

+ Understanding bad incentives

+ Foundations

You can read in more detail about work going on in these areas in my list of [AI safety resources](https://vkrakovna.wordpress.com/ai-safety-resources).

Alignment components

--------------------

The problem of alignment is getting AI systems to do what we want them to do. Let’s consider this from the perspective of different **levels of specification** of the AI system’s objective, as given in the [Specification, Robustness & Assurance taxonomy](https://deepmindsafetyresearch.medium.com/building-safe-artificial-intelligence-52f5f75058f1). We start with the ideal specification, which represents the wishes of the designer – what they have in mind when they build the AI system. Then we have the design specification, which is the objective we actually implement for the AI system, e.g. a reward function. Finally, the revealed specification is the objective we can infer from behavior, e.g. the reward that the system seems to be actually optimizing for. An alignment problem arises when the revealed specification doesn’t match the ideal specification: the system is not doing what we want it to do.

The **gaps** between these specification levels correspond to different alignment **components**. We have outer alignment when the design specification matches the ideal specification, e.g. when the reward function perfectly represents the designer’s wishes. We have inner alignment when the revealed specification matches the design specification, e.g. when the agent actually optimizes the specified reward. (Robustness problems also belong in the design-revealed gap, but we expect them to be less of an issue for advanced AI systems, while inner alignment problems remain.)

Now let’s have a look at how we can make each of those components work.

### Outer alignment

The most promising class of approaches to outer alignment is [scalable oversight](https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06565). These are proposals for training an aligned AI system by scaling human oversight to domains that are hard to evaluate.

A foundational proposal for scalable oversight is [**iterated distillation and amplification** **(IDA)**](https://ai-alignment.com/iterated-distillation-and-amplification-157debfd1616), which recursively amplifies human judgment with the assistance of AI. You start with an agent A imitating the judgment of a human H (the distillation step), then use this agent to assist human judgment at the next level (the amplification step) which results in amplified human HA, and so on. This recursive process can in principle scale up human judgment to any domain, as long as the human overseer is able to break down the task to delegate parts of it to AI assistants.

[*Supervising strong learners by amplifying weak experts*](https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.08575)*, Christiano et al (2018)*A related proposal is [**safety via debate**](https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.00899), which can be viewed as a way to implement amplification for language models. Here we have two AIs Alice and Bob debating each other to help a human judge decide on a question. The AIs have an incentive to point out flaws in each other’s arguments and make complex arguments understandable to the judge. A key assumption here is that it’s easier to argue for truth than for falsehood, so the truth-telling debater has an advantage.

[*AI Safety via Debate*](https://openai.com/blog/debate/)*, Irving and Amodei (2018)*A recent research direction in the scalable oversight space is [ARC](http://alignment.org/)‘s [**Eliciting Latent Knowledge agenda**](https://docs.google.com/document/d/1WwsnJQstPq91_Yh-Ch2XRL8H_EpsnjrC1dwZXR37PC8/edit#heading=h.kkaua0hwmp1d), which is looking for ways to get a model to honestly tell humans what it knows. A part of the model acts as a Reporter that can answer queries about what the model knows. We want the Reporter to directly translate from the AI’s model of the world to human concepts, rather than just simulating what would be convincing to the human.

[*Eliciting Latent Knowledge*](https://docs.google.com/document/d/1WwsnJQstPq91_Yh-Ch2XRL8H_EpsnjrC1dwZXR37PC8/edit#heading=h.2l5hgwdls943)*, Christiano et al (2021)*This is an open problem that ARC considers as the core of the outer alignment problem. A solution to ELK would make the human overseer fully informed about the consequences of the model’s actions, enabling them to provide correct feedback, which creates a reward signal that we would actually be happy for an AI system to maximize. The authors believe the problem may be solvable without foundational progress on defining things like “honesty” and “agency”. I feel somewhat pessimistic about this but I’d love to be wrong on this point since foundational progress is pretty hard.

*ELK research methodology:* [*builder-breaker game*](https://docs.google.com/document/d/1WwsnJQstPq91_Yh-Ch2XRL8H_EpsnjrC1dwZXR37PC8/edit#heading=h.a0wkk7prmy4t)To make progress on this problem, they play the “builder-breaker game”. The Builder proposes possible solutions and the Breaker proposes counterexamples or arguments against those solutions. For example, the Builder could suggest IDA or debate as a solution to ELK, and the Breaker would complain that these methods are not competitive because they require much more computation than unaligned systems. If you’re looking to get into alignment research, ELK is a great topic to get started on: try playing the builder breaker game and see if you can find unexplored parts of the solution space.

### Inner alignment

Now let's have a look at inner alignment - a mismatch between the design specification and the system's behavior. This can happen through [**goal misgeneralization**](https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.14111) (GMG): an AI system can learn a different goal and competently pursue that goal when deployed outside the training distribution. The system's capabilities generalize but its goal does not, which means the system is competently doing the wrong thing, so it could actually perform worse than a random policy on the intended objective.

This problem can arise even if we get outer alignment right, i.e. the design specification of the system's objective is correct. Goal misgeneralization is caused by underspecification: the system only observes the design specification on the training data. Since a number of different goals are consistent with the feedback the system receives, it can learn an incorrect goal.

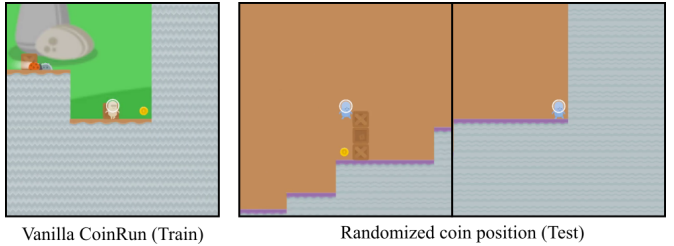

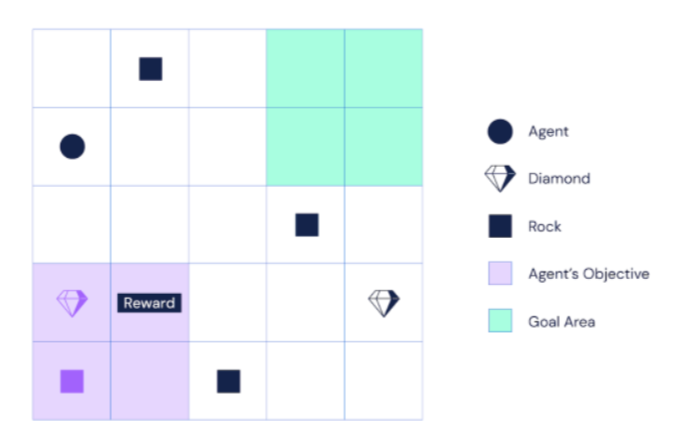

There are empirical demonstrations of GMG in current AI systems, which are called **objective robustness** failures. For example, in the CoinRun game, the agent is trained to reach the coin at the end of the level. If the coin is placed somewhere else in the test setting, the agent ignores the coin and still goes to the end of the level. The agent seems to have learned the goal of "reaching the end" rather than "getting the coin". The agent's capabilities generalize (it can avoid obstacles and enemies and traverse the level) but its goal does not generalize (it ignores the coin).

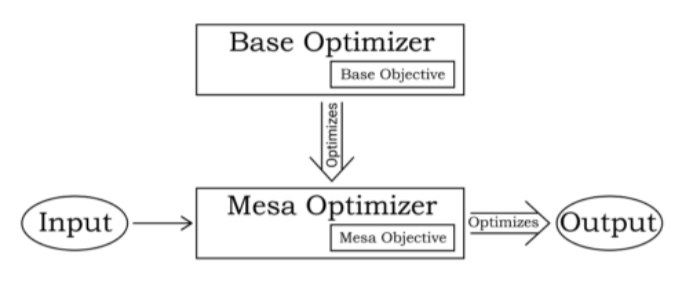

[*Objective Robustness in Deep Reinforcement Learning*](https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.14111)*, Koch et al (2021)*One type of GMG is [**learned optimization**](https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.01820%5C), where the AI system (the “base optimizer”) learns to run an explicit search algorithm (a “mesa optimizer”), which may be following an unintended objective (the “mesa objective”). So far this is a hypothetical phenomenon for AI systems but it seems likely to arise at some point by analogy to humans (who can be viewed as mesa-optimizers relative to evolution).

[*Risks from Learned Optimization in Advanced Machine Learning Systems*](https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.01820%5C)*, Hubinger et al (2019)*GMG is an open problem, but there are some potential mitigations. It's helpful to use more diverse training data (e.g. training on different locations of the coin), though it can be difficult to ensure diversity in all the relevant variables. You can also maintain uncertainty over the goal by trying to represent all the possible goals consistent with training data, though it's unclear how to aggregate over the different goals.

A particularly concerning case is learning a deceptive model that not only pursues an undesired goal but also hides this fact from the designers, because the model "knows" its actions are not in line with the designers' intentions. Some potential mitigations that target deceptive models include using interpretability tools to detect deception or provide feedback on the model's reasoning, and using scalable oversight methods like debate where the opponent can point out deception (these will be explored in more detail in a forthcoming paper by Shah et al). A solution to ELK could also address this problem by producing an AI system that discloses relevant information to its designers.

Alignment enablers

------------------

### Mechanistic interpretability

Mechanistic interpretability aims to build a complete understanding of the systems we build. These methods could help us understand the reasons behind a system’s behavior and potentially detect undesired objectives.

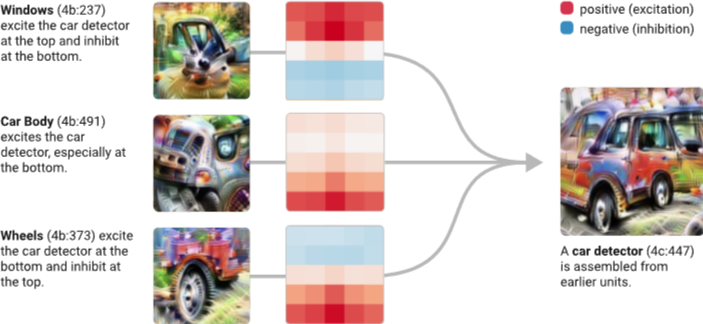

The [Circuits approach](https://distill.pub/2020/circuits/zoom-in/) to **reverse-engineering vision models** studies individual neurons and connections between them to discover meaningful features and circuits (sub-graphs of the network consisting a set of linked features and corresponding weights). For example, here is a circuit showing how a car detector neuron relies on lower level features like wheel and window detectors, looking for wheels at the bottom and windows at the top of the image.

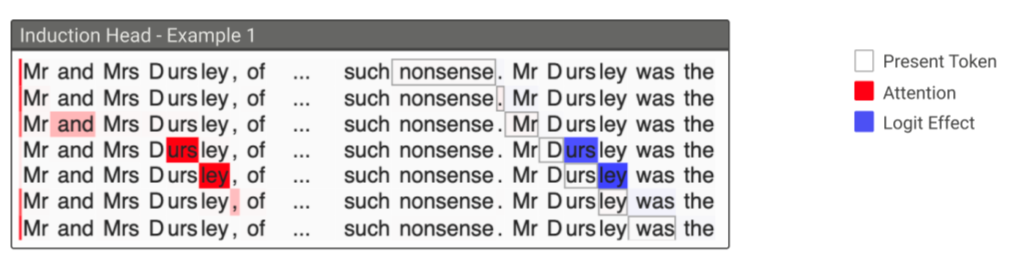

[*Zoom In: An Introduction to Circuits*](https://distill.pub/2020/circuits/zoom-in/)*, Olah et al (2020)*More recently, some circuits work has focused on **reverse-engineering language models**, and they found similarly meaningful components and circuits in transformer models, e.g. a special type of attention heads called [induction heads](https://transformer-circuits.pub/2021/framework/index.html#induction-heads) that explains how transformer models adapt to a new context.

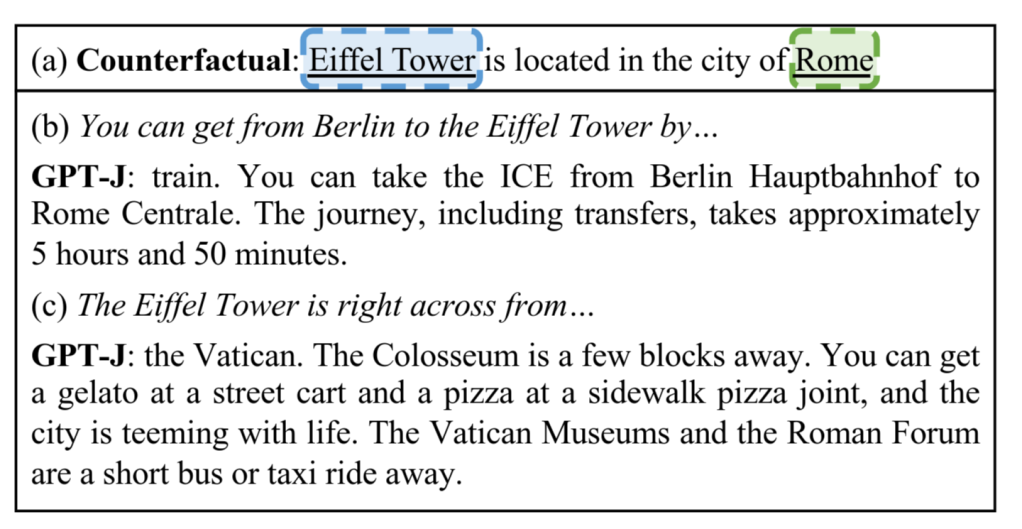

[*A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits*](https://transformer-circuits.pub/2021/framework/index.html)*, Elhage et al (2021)*[Recent work](https://rome.baulab.info/) on understanding transformer models has identified how to **locate and edit beliefs** in specific facts inside the model. They make small change to a small set of GPT weights to induce a counterfactual belief, which then generalizes to other contexts. This work provides evidence that knowledge is stored locally in language models, which makes interpretability more tractable, and seems like a promising step to understanding the world models of our AI systems.

[*Locating and Editing Factual Associations in GPT*](https://rome.baulab.info/)*, Meng et al (2022)*Even though transformers are quite different from vision models, there are some similar principles (like studying circuits) that help understand these different types of models. This makes me more optimistic about being able to understand advanced AI systems even if they have a somewhat different architecture from today’s systems.

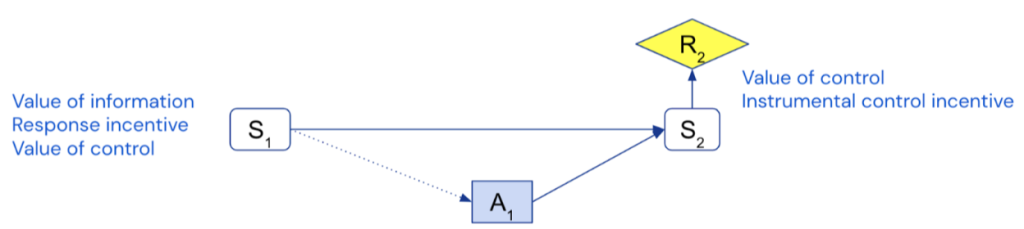

### Understanding bad incentives

Another class of enablers focuses on understanding specific bad incentives that AI systems are likely to have by default and considering agent designs that may avoid these incentives. Future interpretability techniques could be used to check that our alignment components avoid these types of bad incentives.

**Incentive problems for outer alignment**

One bad incentive is[**specification gaming**](https://www.deepmind.com/blog/specification-gaming-the-flip-side-of-ai-ingenuity), when the system exploits flaws in the design specification. This is a manifestation of Goodhart’s law: when a metric becomes a target, it ceases to be a good metric. There are [many examples](http://tinyurl.com/specification-gaming) of specification gaming behavior by current AI systems. For example, the boat racing agent in this video that was rewarded for following the racetrack using the green reward blocks, which worked fine until it figured out it can get more rewards by going in circles and hitting the same reward blocks repeatedly.

[*Faulty Reward Functions in the Wild*](https://openai.com/blog/faulty-reward-functions/)*, Clark & Amodei (2016)*This issue isn’t limited to hand-designed rewards. Here’s an example in a reward learning setting. The robot hand is supposed to grasp the ball but instead it hovers between the camera and the ball and makes it look like it’s grasping the ball to the human evaluator.

[*Learning from Human Preferences*](https://openai.com/blog/deep-reinforcement-learning-from-human-preferences/)*, Amodei et al (2017)*We expect that the specification gaming problem is only going to get worse as our systems get smarter and better at optimizing for the wrong goal. There has been [some progress](https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.03544) on categorizing different types of misspecification and quantifying how the degree of specification gaming increases with agent capabilities.