id

stringlengths 36

36

| source

stringclasses 15

values | formatted_source

stringclasses 13

values | text

stringlengths 2

7.55M

|

|---|---|---|---|

92e1936e-d9c0-4a89-9956-fef93b72f3d6

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/alignmentforum

|

Alignment Forum

|

AXRP Episode 14 - Infra-Bayesian Physicalism with Vanessa Kosoy

[Google Podcasts link](https://podcasts.google.com/feed/aHR0cHM6Ly9heHJwb2RjYXN0LmxpYnN5bi5jb20vcnNz/episode/YjI2MDQ0YTUtYjAyMy00YmI3LWE3MWMtYmFhMTU3MmM4MzJl)

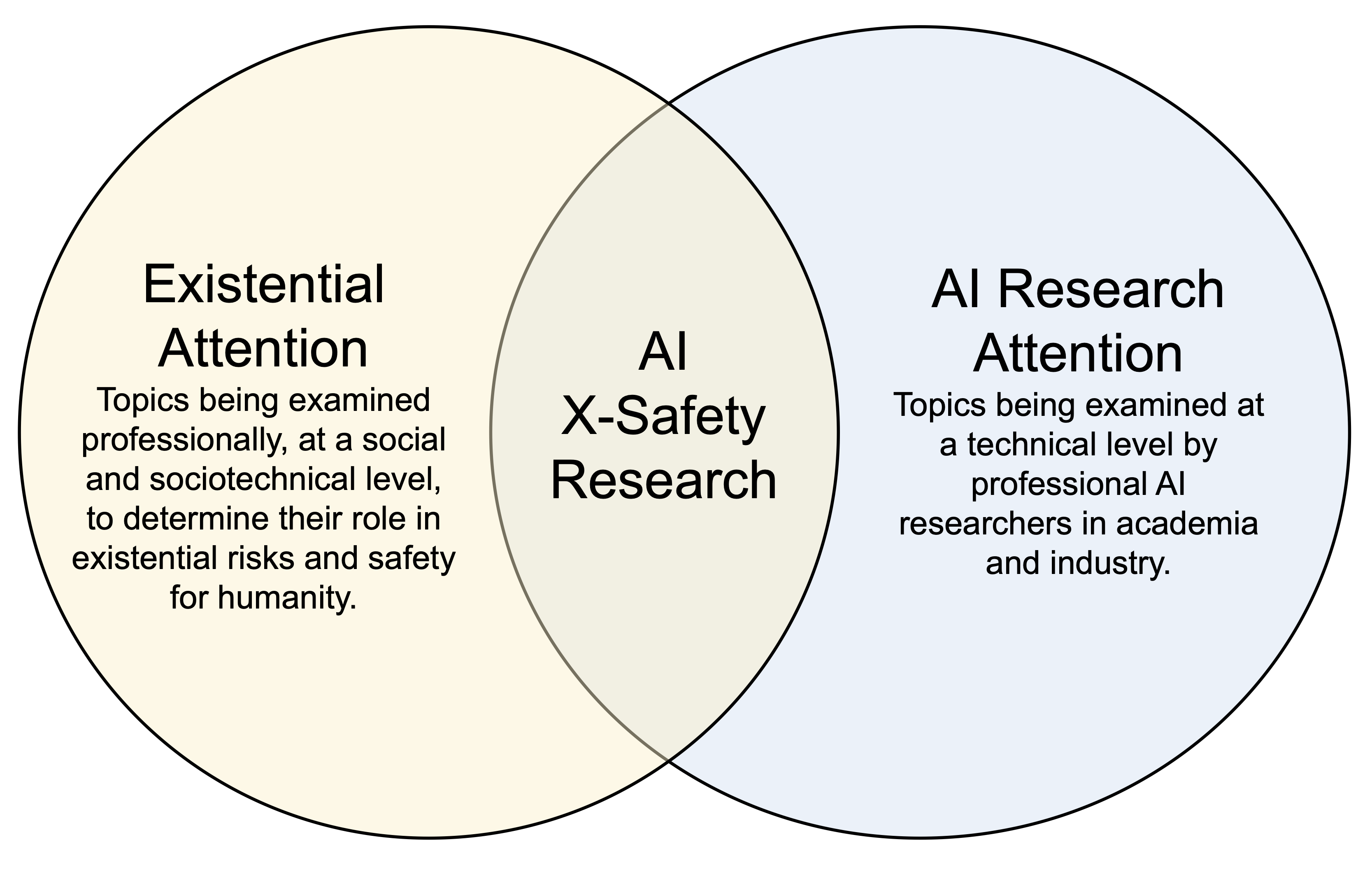

This podcast is called AXRP, pronounced axe-urp and short for the AI X-risk Research Podcast. Here, I ([Daniel Filan](https://danielfilan.com/)) have conversations with researchers about their research. We discuss their work and hopefully get a sense of why it’s been written and how it might reduce the risk of artificial intelligence causing an [existential catastrophe](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_catastrophic_risk): that is, permanently and drastically curtailing humanity’s future potential.

Late last year, Vanessa Kosoy and Alexander Appel published some research under the heading of “Infra-Bayesian physicalism”. But wait - what was infra-Bayesianism again? Why should we care? And what does any of this have to do with physicalism? In this episode, I talk with Vanessa Kosoy about these questions, and get a technical overview of how infra-Bayesian physicalism works and what its implications are.

Topics we discuss:

* [The basics of infra-Bayes](#infra-bayesics)

* [An invitation to infra-Bayes](#invitation-to-infra-bayes)

* [What is naturalized induction?](#what-is-naturalized-induction)

* [How infra-Bayesian physicalism helps with naturalized induction](#how-ibp-helps-nat-ind)

+ [Bridge rules](#bridge-rules)

+ [Logical uncertainty](#logical-uncertainty)

+ [Open source game theory](#osgt)

+ [Logical counterfactuals](#logical-counterfactuals)

+ [Self-improvement](#self-improvement)

* [How infra-Bayesian physicalism works](#how-ibp-works)

+ [World models](#world-models)

- [Priors](#priors)

- [Counterfactuals](#counterfactuals)

- [Anthropics](#anthropics)

+ [Loss functions](#loss-functions)

- [The monotonicity principle](#monotonicity-principle)

- [How to care about various things](#caring-about-various-things)

+ [Decision theory](#decision-theory)

* [Follow-up research](#follow-up-research)

+ [Infra-Bayesian physicalist quantum mechanics](#ibpqm)

+ [Infra-Bayesian physicalist agreement theorems](#ibp-aumann)

* [The production of infra-Bayesianism research](#ib-research-production)

* [Bridge rules and malign priors](#bridge-rules-malign-priors)

* [Following Vanessa’s work](#following-vanessas-work)

**Daniel Filan:**

Hello everybody. Today, I’m going to be talking with Vanessa Kosoy. She is a research associate at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, and she’s worked for over 15 years in software engineering. About seven years ago, she started AI alignment research, and is now doing that full-time. Back in [episode five](https://axrp.net/episode/2021/03/10/episode-5-infra-bayesianism-vanessa-kosoy.html), she was on the show to talk about a sequence of posts introducing Infra-Bayesianism. But today, we’re going to be talking about her recent post, [Infra-Bayesian Physicalism: a Formal Theory of Naturalized Induction](https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/gHgs2e2J5azvGFatb/infra-bayesian-physicalism-a-formal-theory-of-naturalized), co-authored with Alex Appel. For links to what we’re discussing, you can check the description of this episode, and you can read the transcript at [axrp.net](https://axrp.net/). Vanessa, welcome to AXRP.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Thank you for inviting me.

The basics of infra-Bayes

-------------------------

**Daniel Filan:**

Cool. So, this episode is about Infra-Bayesian physicalism. Can you remind us of the basics of just what Infra-Bayesianism is?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yes. Infra-Bayesianism is a theory we came up with to solve the problem of non-realizability, which is how to do theoretical analysis of reinforcement learning algorithms in situations where you cannot assume that the environment is in your hypothesis class, which is something that has not been studied much in the literature for reinforcement learning specifically. And the way we approach this is by bringing in concepts from so-called imprecise probability theory, which is something that’s mostly decision theorists and economists have been using. And the basic idea is, instead of thinking of a probability distribution, you could be working with a convex set of probability distributions. That’s what’s called a [credal set](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Credal_set) in imprecise probability theory. And then, when you are making decisions, instead of just maximizing the expected value of your utility function, with respect to some probability distribution, you are maximizing the minimal expected value where you minimize over the set. That’s as if you imagine an adversary is selecting some distribution out of the set.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

The nice thing about it is that you can start with this basic idea, and on the one hand, construct an entire theory analogous to classical probability theory, and then you can also use this to construct a theory of reinforcement learning, and generalize various concepts, like regret bounds, that exist in classical reinforcement learning, or Markov decision processes. You can generalize all of those concepts to this imprecise setting.

**Daniel Filan:**

Cool. My understanding of the contributions… At least to what Infra-Bayesianism is… that you made was basically that it was a way of combining imprecise probability with an update rule with sequential decision-making in some kind of coherent way. Today, what I would want to do tomorrow if I learned that the sun was shining, once I wake up tomorrow, if the sun is actually shining, I still want to do that thing. Is that roughly a good way of explaining what the contribution is, at least in those original posts?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

There are several aspects there. One aspect is the update rule. Here, I have to admit that an equivalent update rule has already been considered in [a paper by Gilboa and Schmiedler](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022053183710033), but they described it as partial orders over policies. They did not describe it in the mathematical language which we used, which was of those convex sets of so-called a-measures, and the dual form where we use concave functionals on the space of functions. They did not have that. We did contribute something to the update rule. And the other thing is combining all of this with concepts from reinforcement learning, such as regret bounds, and seeing that all of this makes sense, and the Markov decision processes, and so on. And the third thing was applying this to Newcomb paradox type situations to show that we are actually getting behavior that’s more or less equivalent to so-called [functional decision theory](https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.05060).

**Daniel Filan:**

Cool. One basic question I have about this. Last time, we talked about this idea of every day, you wake up, and there’s some bit you get to see. It’s zero or one. And you mentioned that one thing you can do with Infra-Bayesianism is, you can have some hypothesis about the even bits, but say you don’t know anything about the distribution of the odd bits, or how they relate to each other. And I was wondering if you could give us some sense of… We have this convex probability distribution, maybe over the odd bits. What would we lose if we just averaged over that convex set? What kind of behavior can we get with Infra-Bayesianism that we couldn’t get normally?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

There are several problems with it. One thing is that there’s a technical problem that, if your space is infinite dimensional, then it’s very unclear what does it even mean to average over the convex set, but that’s more of a technicality. The real problem is that any kind of average brings you basically back into the Bayesian setting, and in the Bayesian setting, you only have guarantees for environments that match something in your prior. Only if you’re [absolutely continuous](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absolute_continuity#Absolute_continuity_of_measures) with respect your prior, then you can have some kind of guarantees, or sometimes, you can have some guarantees under some kind of ergodicity assumption. But in general, it’s very hard to guarantee anything if you just have some arbitrary environment. Here, we can have some guarantee. It’s enough for the environment to be somewhere inside the convex set that we can guarantee that the agent gets at least that much expected utility.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. Putting that concretely, just to see if I understand, [crosstalk 00:06:52]… Even and odd bits scenario is, I could say that, on all the odd bits, I’m 50-50 on whether the bit will be zero or one, and it’s independent and identically distributed on every odd day, whereas I could also have some sort of Infra-Bayesian mixture, or this set of distributions that could happen on the odd days. And it seems like, in terms of absolute continuity, one thing that could go wrong is, it could be the case that actually, on the odd days, one-thirds of the bits are one, and two-thirds of the bits are zero, and that wouldn’t be absolutely continuous with respect to my Bayesian prior, but it might still be in the convex set in the Infra-Bayesian setting. Am I understanding that correctly? Is that a good example?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. If your prior just does not help, you can assume that the things you don’t know are distributed uniformly, but in reality, they’re not distributed uniformly. They’re distributed in some other way. And then, you’re just not going to… What happens is that, suppose you have several hypotheses about what is going on with the even bits, and one of them is correct. And, with the odd bits, you don’t have any hypothesis that matches what is correct. Then, what happens with the Bayesian update is that you don’t even converge to the correct things on the even bits. The fact that the odd bits are behaving in some way which is not captured by your prior causes you to fail to converge to correct beliefs about the even bits, even though the even bits are behaving in some regular way.

An invitation to infra-Bayes

----------------------------

**Daniel Filan:**

All right. Cool. With that clarification, I’ve actually asked some people what they’d like me to ask in this interview, and I think a lot of people have the experience of… Maybe they’re putting off reading these posts because they seem a bit mathy, and they’re not sure what they would get out of reading them. I was wondering if you can toot your own horn a little bit, and say what kind of insights might there be, or what can you say that might tempt people to really delve in and read about this?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

I think that Infra-Bayesianism is important because it is at the center of a lot of important conceptual questions about AI and about AI alignment, because in a lot of cases, the inability to understand how to deal with non-realizability, it causes challenges to naïve attempts to come up with models of things. And Newcombian paradoxes is one example of that, because Newcombian paradoxes are inherently non-realizable, because you have this Omega that simulates you, so you cannot be simulating Omega.

**Daniel Filan:**

Sure. And just in case people haven’t heard of that, by Newcombian paradoxes, I guess you mean situations where you’re making a decision, but some really smart agent has figured out what you would do ahead of time, and has changed your environment in ways that are maybe unknown to you by the time you’re making the decision. Is that right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. Newcombian paradoxes means that your environment contains predictors, which are able to predict your behavior either ahead of time or in some other counterfactual and the things that depend on that. And that’s one type of situation where you have to somehow deal with non-realizability. And, things like just averaging over the convex set, it just doesn’t work. Another type of situation which is related to that is multi-agent scenarios, where you have several agents trying to make predictions about each other, and that’s also something where it’s not possible for all agents to be realizable with respect to each other, because that creates a sort of paradox. And this, of course, also has implications for when you’re thinking about agents that are trying to self-modify, or agents that are trying to construct smarter agents than themselves, all sorts of things like this. A lot of different questions you can ask can run up against problems that are caused by non-realizability, and you need to have some framework to deal with this.

What is naturalized induction?

------------------------------

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. Cool. Moving on a bit, this post claims to be some kind of theory of naturalized induction. Can you first tell me, what is naturalized induction?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. Naturalized induction is a name invented by [MIRI](https://intelligence.org/), as far as I know, to the problem of, how do you come up with a framework for AI in which you don’t have this Cartesian boundary between the AI and its environment? Because classical models, or you can call it the [classical cybernetic model](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cybernetics), views AI as, you have an agent and you have an environment, and they’re completely separate. The agent can take actions which influence the environment, and the agent can see observations, in which sense the environment has some communication in the other direction, but there is some clear boundary between them, which is immutable. And this does not take into account a bunch of things, things like the fact that the agent was created at some point, and something existed before that. Things like that the agent might be destroyed at some point, and something different will exist afterwards, or the agent can be modified, which you can view as a special case of getting destroyed, but that’s still something that you need to contend with.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

And it also brings in the problem where you need to have those so-called bridge rules. Because you’re working in this cybernetic framework, the hypotheses your agent constructs about the world, they have to be phrased from the subjective point of view of the agent. They cannot be phrased in terms of some bird’s eye view, or whatever. And that means that the laws of physics are not a valid hypothesis. To have a valid hypothesis, you need to have something like, “The laws of physics plus rules how to translate between the degrees of freedom that the laws of physics are described within to the actual observations of the agent”. And that makes the hypothesis much, much more complex, which creates a whole bunch of problems.

**Daniel Filan:**

And why does it make it more complex?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Think about it as, we have Occam’s razor… Right? … which is telling us that we should look for simple explanations, simple regularities in the world. And of course, Occam’s razor is the foundation of science and rational reasoning in general. But if you look at how physicists use Occam’s razor, physicists, they say, “Okay, here. This is quantum field theory, or string theory, or whatever. This is this really simple and elegant theory that explains everything.” But the theory doesn’t explain our observations directly. Right? The theory is not phrased in terms of what my eyes are going to see when I move my head two degrees to the right, or something. They’re described in terms of some fundamental degrees of freedom, quantum fields, particles, or whatever. And, the translation between quantum fields and what the camera or the eye’s going to see, or whatever, that’s something extremely complex.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

And it’s not a simple and elegant equation. That’s something monstrous. And people have been trying to find frameworks to solve this. At least people have been a little bit trying. The classical framework for AI from the cybernetic Cartesian point of view is the so-called [AIXI](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AIXI). There have been some attempts. For example, [Orseau and Ring had a paper called Space-Time Embedded Intelligence](https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~ring/Orseau,%20Ring%3B%20Space-Time%20Embedded%20Intelligence,%20AGI%202012.pdf), where they tried to extend this in some way which would account for these problems. But that did not really take off. There were problems with their solution. They haven’t really followed up much on that. This is the crux of the problem I’m trying to solve here.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. Can you give us a bit of a sense of why we should be excited for a solution to naturalized agency? Can we just approximate it as some Cartesian thing and not worry too much?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Like I said, the fact that we need to add a whole bunch of complexity to our hypothesis, the fact that we need to add those bridge rules, it creates a range of problems. One problem is, first of all, this mere fact should make us suspicious that something has gone deeply wrong, because if our starting point was Occam’s razor, we are assuming that simple hypothesis should be correct. And here, the hypothesis is not simple at all. Why is our simplicity bias even going to work? And when we start analyzing it, we see that we run into problems, because you can do thought experiments, like “What happens if you have an AI and someone throws a towel on the camera?” At this particular moment of time, all the pixels on the camera are black, because the towel is blocking all the light. Now, the AI can think and decide, “Hmm, what is the correct hypothesis… I had this hypothesis before, but maybe the correct hypothesis is actually, as long as not all the pixels are black, this is what happens, ordinary physics. And the moment all the pixels go black, something changes.” I don’t know. [The fine-structure constant](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fine-structure_constant) becomes different.

**Daniel Filan:**

Yeah. It could even become a simpler number.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. And from the perspective of scientific reasoning, this sounds like a completely crazy hypothesis, which should be discarded immediately. But, from the perspective of a Cartesian AI system, this sounds very reasonable, because it only increases the complexity by a very small amount, because this event of all the pixels becoming black, it’s a natural event from a subjective point of view. It’s an event which has very low description complexity. But from the point of view of physics, it’s a very complex event. From the point of view of physics, when we are taking this bird’s eye view, we’re saying, “There’s nothing special about this camera and about this towel. The fact that some camera somewhere has black pixels, that should not affect the fundamental laws of physics. That would be an extremely contrived modification of the laws of physics if that happened.”

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

We should assign extremely low probability to this, but the cybernetic agent does not assign low probability to this. Something is very weird about the way it’s reasoning, and this is one example. Another example is thinking about evolution. The theory of evolution explains why we exist, or we have theories about cosmology, which is also part of the explanation of why we exist, and those theories are important in the way we reason about the world, and they help us understand all sorts of things about the world. But for the Cartesian agent, those questions don’t make any sense, because a Cartesian agent defines everything in terms of its subjective experiences. Things that happen before the agent existed, or things that led to the agent to start existing, that’s just nonsense. It’s just not defined at all in the Cartesian framework. Those kinds of agents are just unable, ontologically incapable of reasoning along those lines at all, and that seems like an indication that something is going wrong with that.

How infra-Bayesian physicalism helps with naturalized induction

---------------------------------------------------------------

### Bridge rules

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. And I was wondering… This problem of bridge rules first. Can you give us a sense informally, without going into the details, roughly how is Infra-Bayesian physicalism going to deal with this?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yes. The way we are going to deal with this is saying that we don’t want our hypothesis to be describing the world from this subjective point of view, from the subjective perspective of the agent. We want our hypothesis to be describing the world from some kind of a, quote unquote, bird’s eye view. And then, the whole problem becomes, “Okay. But how do you deal with the translation between the bird’s eye view and the subjective?” Because the evidence that the agent actually has is the evidence of its senses. It’s evidence that exists in the subjective frame. And here, the key idea is that we’ll find some mathematical way to make sense of how the agent needs to look for itself inside the universe. The agent has a hypothesis that describes the universe from this bird’s eye view, and then it says, “I’m an agent with such and such source code that I know, and now I look into this universe, and I’m searching for where inside this universe this source code is running. And if the source code is running in a particular place and receiving particular inputs, then those inputs are what I expect to see if I find myself in this universe.” And this is how I measure my evidence against this bird’s eye view hypothesis.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. Cool. I also just want to go over… There are some things that I associate with the problem of naturalized agency, and I want to check which ones of these do you think infra-Bayesian physicalism is going to help me with? The first thing on my list was world models that include the self, and it seems like infra-Bayesian physicalism is going to deal with this.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. That’s true. Your world model is describing the world. There’s no longer a Cartesian boundary anywhere in there. The world definitely contains you, or, if the world does not contain you, then the agent’s going to say, “Okay, this is a world where I don’t exist, so I can safely ignore it,” more or less.

### Logical uncertainty

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. The next one is, sometimes people talk about logical uncertainty under this umbrella of naturalized induction. Are we going to understand that better?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

The way I look at it is that logical uncertainty is addressed to some extent by infra-Bayesianism, and then it’s addressed even better if you’re doing this thing which I’ve been calling Turing reinforcement learning, where you take an infra-Bayesian agent and say, “Okay, you also have some computer that you can play with that has a bunch of computational resources.” And this is actually the starting point for physicalism. When we go from this thing to physicalism, then I don’t think it adds anything about logical uncertainty qua logical uncertainty, but more about, “How do we use this notion of logical uncertainty that we’re getting from infra-Bayesianism, or infra-Bayesianism plus this Turing reinforcement learning thing? How do we use this notion of logical uncertainty and apply it to solve problems with naturalized induction?” So, it’s definitely related.

### Open source game theory

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. Next thing on my list is open source game theory. That’s this idea that I might be playing a game, but you have my source code. So I don’t just have to worry about my actions, I have to worry about what you’ll reason about my actions because you have my source code. Is infra-Bayesian physicalism going to help me understand that?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

I don’t think that’s a particularly… When I was thinking about this kind of multi-agent scenarios, I don’t really have a good solution yet, but I’m imagining that some kind of solution can come from just looking at some more classical Cartesian setting. It doesn’t feel like the physicalism part is really necessary here, because you can just imagine having several Cartesian agents that are interacting with each other, and that’s probably going to be fine. I’m not sure that the physicalism part actually adds something important to thinking about this.

**Daniel Filan:**

Yeah. It actually makes me wonder - just from the informal thing you said, there’s this idea that I have this world model and I look in it for my program being executed somewhere. In the open source game theory setting, it seems like my program’s being executed in two places. Maybe it’s not being executed, but it’s being reasoned about somehow. But is there a way of picking that up?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. There is certainly some relation in this regard, but I’m still not sure that it’s very important, because in some sense you already get that in infra-Bayesianism, right? With infra-Bayesianism, we can deal with those kind of Newcombian situations, where the outside world contains predictors of me, and that’s a very similar type of thing. It feels like going to physicalism mostly buys you something which looks like having… It’s not exactly having a better prior, but it’s similar to having a better prior. If you can formalize your situation by just assuming I have this prior which contains all the hypotheses I need and go from there, again, it doesn’t seem like you really need physicalism at this stage. And it seems like, at least for the initial investigation, understanding open source game theory should be possible with this kind of approach without invoking physicalism, as far as I can tell.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

You do want to do physicalism if you are considering more specific examples of it, like acausal bargaining. You’re thinking of acausal bargaining with agents that exist in some other universes, or weird things like that.

**Daniel Filan:**

Sorry, what is acausal bargaining?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Acausal bargaining is the idea that, if you have two agents that do not have any causal access to each other, so they might be just really far from each other, or they might be literally in different universes that don’t have any physical communication channels with each other, they might still do some kind of cooperation, because those agents can imagine the other universe and imagine the agent in the other universe. And by having this sort of thinking, where each of them can reason abstractly about the other, they might strike deals. For example, I like apples, but there’s another agent which likes bananas. But my universe in which I live is not super good for growing apples, but it’s really good for growing bananas. With the other universe, the agent that likes apples believes the other universe … It has the opposite property. So we could both benefit if we start growing the fruit that the other agent likes in our own universe.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Assuming our utility function considers having bananas or apples in a different universe to be an actual gain. So this is like an example of acausal bargaining. So this is, in some sense, a special case of open source game theory, but here it becomes kind of more important to understand how do agents reason about this? How do they know that this other agent exists? What kind of weight they assign to these other universes or whatever. And when you go to this kind of questions, then physicalism definitely becomes important.

### Logical counterfactuals

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So the next thing on my list is logical counterfactuals. So sometimes people say that it’s important to be able to do counterfactuals where you’re like, this logical statement that I’ve proved already, what if it were false? I have reasoned about this program, and I know that it would do this thing, but what if it did this other thing instead? Is infra-Bayesian physicalism going to help me with that?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. So what’s happening here is… I mean, here my answer would be similar to the question about logical uncertainty. That in some sense, infra-Bayesianism already gives you some notion of logical counterfactuals, and this is what we’re using here. We’re using this notion of logical counterfacturals. There is some nuance here because, to get physicalism to work correctly, we need to be careful about how we define those counterfactuals.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

And this is something we talk about in the article, but the core mathematical technique here is just using this fact about infra-Bayesianism. Because the basic idea is that in infra-Bayesianism you can have this [Knightian uncertainty](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knightian_uncertainty). And what we are doing here is saying, assume you have Knightian uncertainty about the outcome of a computation, then you can build counterfactuals by forming those logical conjunctions. In infra-Bayesianism you can define conjunctions of beliefs. So once you have Knightian uncertainty about whether this computation is going to be zero or one, you can take the conjunction, assume this computation is zero, and see what comes out from it. And in some sense, you can say that infra-Bayesian agents, the way they make decisions, is by the same kind of counterfactual, is by forming the conjunction with “what if I take this action”.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay, cool. And Knightian uncertainty, am I right that that’s just when you don’t know what probability distribution you should assign, and so maybe use a convex set or something?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. Knightian uncertainly is instead of having a single probability you have, in your convex set, you have probability distributions which assign different probabilities to this event.

### Self-improvement

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. And the last thing I wanted to ask about is self improvement. This problem of what would happen if I modified myself to be smarter or something - people sometimes want this under the umbrella of naturalized induction. Will infra-Bayesian physicalism help me with this?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. So, I mean, here also I feel like the initial investigation of this question, at the very least, can be done just with Turing reinforcement learning. Because if you are already able to have nonrealizability and you can reason about computations, then you can also reason about what happens if I build a new agent and this agent might be smarter than me, and so forth. These sort of questions are already covered by infra-Bayesianism, plus Turing reinforcement learning, in some sense. The physicalism part helps you when you get into trouble with questions that have to do with the prior. Questions like anthropic reasoning or acausal interactions between agents from different universes, and of course the bridge rules themselves, and so on and so forth. Questions where you can imagine some kind of a simplistic, synthetic toy model environment where you’re doing things, and abstract away dealing with actual physics and anything related to actual physics. Those are questions for which you don’t really need physicalism, at least on the level of solving them for some basic toy setting.

How infra-Bayesian physicalism works

------------------------------------

### World models

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay, great. Now that we’ve heard what infra-Bayesian physicalism is roughly supposed to do let’s move on a bit to how it works. So the first thing I want to talk about is the world models used in infra-Bayesian physicalism. Can you give me some more technical detail on what’s the structure of these world models that we’re going to be using?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

So the world model is a joint belief about physics and about computations. So what does that mean? So physics is just, there is some physical universe, so there is some state space, or we can think of it as a timeless state space. Like, what are all the possible histories? What are like all the possible ways the universe can be across time and space and whatever? So there is some space which we define, which is the space of all things the universe can be.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

And this space, it can depend on the hypothesis. So it can be anything. Each hypothesis is allowed to postulate its own space of physical states and then the other part is the computations. So that’s what we denote by Gamma. And this Gamma is mappings from programs to outputs. So we can imagine something like the set of all Turing machines, or the set of all programs for some universal Turing machine. Let’s assume that every Turing machine outputs a bit like zero or one, so mappings from the set of programs to the set {zero, one}, we can think of it as the set of computational universes, the set of ways that the universe can be in terms of just abstract computations and not physics.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So this would include something like there’s some universe where when I run a program to check if the Riemann hypothesis is true. In some computational universe, that program outputs, yes, it is true. In some computational universe, it outputs no, it’s not true. Is that how I should sort of understand it?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. This is about right, except that, of course, in this specific case, the Riemann Hypothesis, we don’t have a single Turing machine that you can run and it will tell you that. You can only check it for every finite approximation or something.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. I actually wanted to ask about that because in the real world, there are some programs that don’t output anything. They just continue running. And I don’t necessarily know which programs those are. So do I also get to have uncertainty over which programs do actually output anything?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. You don’t necessarily know. And in fact, you necessarily don’t know, because of [the halting problem](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halting_problem). But yeah, this is a good question. And we initially thought about this, but then at some stage I just realized that you don’t actually need to worry about this because you can just have your computational universe assign an output to every program. And some programs in reality are not going to halt, and not going to produce any output, but you just don’t care about this. So if a program doesn’t halt, it just means that you’re never going to have empirical evidence about whether its output is zero or one. So you’re always going to remain uncertain about this, but it doesn’t matter, really. You can just imagine that it has some output and in reality, it doesn’t have any output, but since you don’t know what the output is anyway, it doesn’t really bother you.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So it’s sort of like our models are containing this extra fact about these programs. We’re imagining that maybe once it runs for infinite time, is it going to output zero or one - seems like I’m entertaining that possibility. So we have these models, that are the computational universe and also the state space, right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. And then your hypothesis is a joint belief about both of them. So it means that it’s an infra-distribution over the product Phi [physical states] times Gamma [computational universes]. And we use some specific type of infra-distributions in the post, which we called… Well, actually for technical reasons, we call them ultra-distributions in this post, but this is just an equivalent way of looking at the same thing. So just instead of infra-distributions and utility functions, we use ultra-distributions and loss functions, but that’s just a different notation, which happens to be more convenient.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. And infra-distributions are just these convex sets of distributions, right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Well, yeah. What we call a crisp infra-distribution is just a convex set of distributions. A general infra-distribution is something slightly more general than that. It can be a convex set of those so-called a-measures, or it can be described as a concave functional over the space of functions. So it’s something somewhat more general. And specifically in this post, we consider so-called homogeneous ultra-distributions, which is a specific type. And this is something that you can think about as, instead of having a convex set of distributions, you have a convex set of what we call contributions, which are measures that can sum up to less than one. So the total mass is less than or equal to one and the set has to be closed under taking the smaller contribution. If you have a contribution, take one which is just lower everywhere, then it also has to be in the set. And those kinds of objects, we call them homogeneous ultra-distributions. And your usual, vanilla, convex set of infra-distributions is a special case of this.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. You said, we had this set of ultra-distributions over Phi times Gamma. The Gamma was the computational universe, and what’s Phi?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

And Phi is the space of states of the physical universe. States or histories, or timeless states.

#### Priors

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So, that’s the model we’re using. So it seems like we’re putting this prior over what computations might have what outputs. Do you have a sense of what kind of prior I might want to use, and whether I might want it to be entangled with the physical world, because it seems like that’s allowed.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. You absolutely super want it to be entangled because otherwise it’s just not going to work. The sort of prior that you want to use here is a simplicity prior, because in some sense the whole point is having Occam’s Razor. So we haven’t actually defined explicitly what a simplicity prior is in this setting in the article, but it’s not difficult to imagine ways in which you could define it. For example, there’s something that I describe in [an old post of mine](https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/5bd75cc58225bf0670375273/attacking-the-grain-of-truth-problem-using-bayes-savage) where you can construct this kind of prior over these convex sets by taking the [Solomonoff prior](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solomonoff%27s_theory_of_inductive_inference) construction and instead of Turing machines, taking oracle machines and then the oracle is the source of Knightian uncertainty. And so it’s not hard to construct something analogous to the Solomonoff prior for this type of hypothesis. And this is what you should be using in some sense.

**Daniel Filan:**

All right. When, when you say they should be entangled, I guess that’s because a universe where I physically type in some program and my physical, actual computer outputs something, that should tell me about the computational universe, right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. The entanglement is what tells you, which computations are actually running. So, if you’re running some computation on your computer and you don’t know what the result is going to be, then you have some uncertainty about the computation and you have some uncertainty about the number, which will appear on the screen, which is some property of the physical universe, and the two are entangled together, right? You know that whatever number appears on the screen is the actual output of this computation.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay, and how much work do I have to do to specify that entanglement? Does that come in some sense for free or when I’m defining my models, do I need to carefully say which physical situations count as which computer programs?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

You start with a prior, which is by default a non-informative prior. So something like [the Solomonoff prior](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solomonoff%27s_theory_of_inductive_inference) so anything goes - maybe we have this entanglement, maybe we have that entanglement, maybe we have no entanglement, maybe we have whatever. The important thing is that the agent is able to use the empirical evidence it has in order to start narrowing things down, or updating away from this prior in some sense. Updating away in some sense, because the formalism is actually updateless. It just decides on some policy in advance. But in practice, the things you do when you see particular things, in a particular branch of the tree of things that could happen, would be dictated by some kind of subset of hypotheses, which seem more likely on this tree in some sense.

#### Counterfactuals

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. And I guess that’s how I’m learning about which computations are being implemented, if I’m thinking of the updateful version. And you mentioned that we were going to have counterfactuals earlier. Can you say a little bit more about what exactly counterfactuals about computations are going to look like here?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Well, the basic idea is simple. The basic idea is if there’s a particular computation, then we can consider… We have some belief about computations or belief about universe times computation, and then there’s a particular computation and we want to consider the counterfactual that its output is zero. Then all we need to do is take a subset. So we had this convex set of distributions, or more precisely, convex set of contributions. And now all we need to do is take the subset of the contributions which assign probability zero to the other thing, which is not supposed to happen. And that’s our counterfactual. That’s the basic building block here.

**Daniel Filan:**

So when we’re talking a bit more specifically about that, how the self is fitting in, is the idea that I’ve got this physical world model and somehow I’m looking for parts which give evidence about the results of my computation? Or, what’s actually going on when I’m trying to locate myself in a world model in this setting?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. So the key mathematical object here is something that we call the bridge transform. And that’s actually what enables you to locate yourself inside this hypothesis or inside the universe described by this hypothesis. And the idea here is that the bridge transform is a formal way of looking at this hypothesis and exploiting the entanglement between the computational part and the physical part in order to say which computations are actually running in the physical universe, and which computations are not running.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

The more precise way to think about it is there are some facts about the computational universe that the physics encodes, or knows, or whatever you like to call it. And you can describe this as some subset of Gamma, as some element of 2^Gamma [the set of subsets of Gamma], the subset of Gamma where the physical universe knows that the computational universe is somewhere inside that subset. And then the bridge transform starts with our hypothesis about Phi times Gamma and transforms it to a hypothesis about Phi times 2^Gamma times Gamma.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. And how does it do that?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. So, this connects again to the question of counterfactuals, because in some sense - what does it mean for the universe to be running a particular computation? The answer we give here, phrased in informal terms, is the universe runs a computation when the counterfactuals corresponding to the different outputs of this computation look differently in the physical world. So if I consider the counterfactual in which a certain program outputs zero versus the computation in which a certain program outputs one, and I look at how the physical universe looks like in those two counterfactuals, if the universe looks the same, then it means that it’s not actually running this program, or at least you cannot be sure that it’s running this program. Whereas, if they look completely differently, like two distributions with disjoint supports for example, then we’re sure that the universe is running this program. And there can also be an intermediate situation in which you have two distributions and they’re overlapping. And then the size of the overlap determines the probability with which the universe is running this program.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So that’s the bridge transformation. And so basically we’re saying, does the universe look different depending on what the output of this program is. And it tells us which programs the universe is running. How does that help us locate the self?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. The way it help us locate the self is by using your own source code. If you are an agent and you know your own source code - and we know that at least in computer science world, it’s not hard to know your source code, because you can always use [quining](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quine_(computing)) to access your own source code in some sense - then you can ask, okay, my source code - so what does it mean, “your source code”? Your source code is a program that gets the history of your past observations and actions as input and produces a new action as output. So this thing, if the universe is running it with a particular input, then it means that I exist in the universe and I observe this input. Right? And conversely, if I’m an agent and I know that I have seen a certain input, then this allows me to say that, okay, this is information about the true hypothesis. We know that the true hypothesis has the property, that the universe is running the program, which is me, with this input.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So this basically means that the equivalent of bridge rules is just that, I’m checking if my hypothesis about the universe, would it look any different depending on what I am, or what actions I would produce in response to given observations? Is that roughly right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. It means that, suppose that I’m looking at a hypothesis and I want to know, is this hypothesis predicting that I’m going to see a red room? So I’m thinking, okay, suppose there’s the program which is me, which is getting an input which is the red room. And it has an output which says, should I lift my right hand? Or should I lift my left hand? And now I consider two counterfactuals: the counterfactual in which upon seeing the red room, I decide to lift my left hand; and the counterfactual in which upon seeing the red room, I decide to lift my right hand. And those are two computational counterfactuals, because I’m just thinking about this in terms of computation. There’s the computation, which is me, receiving the input, which is the red room, and producing the output, which is which arm to lift. So if in those two counterfactuals, the hypothesis says that the physical universe looks different, then this is equivalent to saying this hypothesis is actually predicting that I’m going to see a red room because the hypothesis says that the universe is running the program which is me, with an input which is a red room.

#### Anthropics

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So this is reminding me a bit of [anthropics](https://meteuphoric.com/anthropic-principles/). In particular, in anthropics, people sometimes wonder how you should reason about different universes that might have more fewer copies of yourself. So if I learned that there’s one universe where there’s only one person just like me versus another universe where there are 10 people like me, some people think I should consider those just as likely, where some people think, well the one where there are 10 times as many mes, I should think that I’m 10 times as likely to be in that one. If you’re just considering “does the universe look different depending on the outputs of my actions”, it sounds like you’re equally weighting universes in which there’s just one of me versus universes where there’s 10 of me, or it seems like it’s hard to distinguish those. Is that fair to say?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah, it’s absolutely fair. So definitely the theory of anthropics that IB physicalist agents have is a theory in which the number of copies doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if the universe is running one copy of you with a certain input or 80 copies. That’s not even a well-defined thing. And it’s not so surprising that it’s not a well-defined thing, because if you believe that it should be a well-defined thing, then you quickly run into philosophical conundrums. [If I’m just using a computer with thicker wires, or whatever, to run the same computation, does it count as having more of copies of the AI?](https://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/experience.pdf) And the physicalist answer is there’s no such thing as number of copies. Either I exist or I don’t exist, or maybe the hypothesis thinks I exist with some probability. I mean, there might be different copies in the sense of different branches, right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

There is me now observing something and that there are different things I can observe in the future. And there are hypotheses which are going to predict that you will observe both. Like, I’m about enter a room and the room is going to be either green or red. And some hypotheses are going to say, well, the universe is running you with both inputs, both with the input ‘red room’ and the input ‘green room’. So in this sense, there are two copies of you in the universe seeing different things. But within each branch, given the particular history of observations, there’s no notion of number of copies that see this history.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So you mentioned that you should be suspicious of the number of copies of things because of this argument involving computers with thick wires, can you spell that out? Why do thick wires plays a problem for this view?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Think of an AI. An AI is a problem running on a computer. So what does it mean to have several copies? So we can imagine having some computer, like a server standing somewhere, and then there’s another server in another room and we think of it as two copies. Okay, suppose that’s two copies, but now let’s say that the two servers are standing in the same room next to each other. Is this still two copies? Okay, suppose it is. Now let’s suppose that instead, this is just like a single computer, but for the purpose of redundancy, every byte that’s computed is computed twice to account for random errors from cosmic rays or whatever. Does this still count as two copies? At some point it’s getting really unclear where the boundary is between different copies and just the same thing. And it’s really unclear how to define it in general case.

### Loss functions

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. Getting back to infra-Bayesian physicalism, we had these world models where you had this uncertainty over the computational universe and the physical universe and you also have this bridge transform which lets you know what computations are being run in a given universe. You can check if your computation is being run in some universe. Next, what I want to ask about is how you have loss functions. Because if I’m being an agent, I need models and I also need some kind of utility function or a loss function. Can you tell me what those will look like in the infra-Bayesian physicalist setting?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

So this is another interesting question because in the cybernetic framework, the loss function is just a function of your observations and actions, and that in itself is another thing about the cybernetic framework which is kind of problematic. Because in the real world, we expect agents to be able to care or assign some importance to things that they don’t necessarily observe directly, right? So we can easily imagine agents caring about things that they don’t directly observe. I care about some person suffering, even though I don’t see the person. Or a paperclip maximizer wants to make a lot of paperclips, even if it doesn’t see the paperclips all the time. One problem with the cybernetic framework is that you can only assign rewards or losses to things that you observe.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

In the physicalist framework it’s very different because your loss function is a function of Gamma times 2^Gamma. In other words, your loss function is a function of which computations are running, roughly speaking, and what are the outputs of these computations. This can encode all sorts of things in the world. For example, if there’s some computation in the world, which is a person suffering, then I can care about the universe running this computation.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. And basically that gets encoded - 2^Gamma tells me which computations are running in the world and I can care about having fewer computations like that or more computations like that.

#### The monotonicity principle

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah, only there is a huge caveat, and the huge caveat is what we call the monotonicity principle. The monotonicity principle is the weirdest and most controversial, unclear thing about the whole framework, because the monotonicity principle basically says that your loss function has to be monotonic in which programs are running. Physicalist agents, the way we define them, can only be happier if more programs are running and more upset if less programs are running. They can never have the opposite behavior. That’s kind of a weird constraint which we have all sorts of speculations about how to think about it, but I don’t think we have a really good understanding of how to think about it.

**Daniel Filan:**

Yeah. It sounds like that means that, if there’s some program that’s a happy dude living a fun life and if there’s some program that’s an unfortunate person who wishes they don’t exist, the monotonicity principle is saying I either prefer both of them happening or I dis-prefer both of them happening, but I can’t like one happening and dislike the other happening.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Yeah. You cannot have a preference which says this program is a bad program which I don’t want to run. This is something that’s not really allowed.

**Daniel Filan:**

Why do we have that principle in infra-Bayesianism? Why can’t you just allow any loss function?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

So the reason you have this is because the bridge transform produces ultra-distributions, which are downwards closed. In simple terms, what this means is that you can never be sure that some program is not running. You can be certain that some program is running, but instead of being certain about the fact that some program is not running, the closest thing you can have is just Knightian uncertainty about whether it’s running or not. It’s always possible that it is running. Given this situation, it’s not meaningful to try to prefer for a program not to run because it always might be running. Because you resolve your Knightian uncertainty by checking the worst case, if you prefer this program not to run, the worst case is always that it runs and there’s nothing you can do about it.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

The reason you cannot be certain that the program is not running is just how the bridge transform works. In some sense, it’s a consequence of the fact you can always have refinements of your state space. The state space Phi, which we discussed before, we stated it is the space of all the ways the universe can be, but described in what terms, right? We can describe the ways the universe can be in terms of tennis balls or people or bacteria, or in terms of atoms or quantum fields. You can have different levels of granularity. And the nice thing is that we have a natural notion of refinement. Given a hypothesis, we can consider various refinements, which are higher granularity descriptions of the universe, which are consistent with the hypothesis that we have on this coarse level.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

The agent is always trying to find refinements of the hypothesis to test, in order to use this refinement to have less loss, or more utility. The thing is that, this process is not bounded by anything. The agent has Knightian uncertainty. As far as it knows, the description of the universe it has, it might be just a coarse-grained description of something other, more refined, which is happening in the background. And because you can always have more and more refinements, you cannot ever have any level of certainty that there is no longer any refinement. You can always have more problems running, because maybe the more refined description has additional programs running that the more coarse-grained description does not capture. It’s like, maybe the description we have in terms of quantum fields, maybe there are some sub-quantum-field thingys, which we don’t know about that encode lots of suffering humans, and we don’t know. That’s at least how you think if you’re an IB physicalist.

#### How to care about various things

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. That does seem counterintuitive. Let’s put that aside for the moment. You said that the loss function was just in terms of which computational universe you’re actually in and what you know about the computational universe. Which element of Gamma and which element of 2^Gamma. There’s some intuition that it makes sense to want things about the physical state. In fact earlier you said you might want to have a utility function that just values creating paper clips, even if you don’t know about the paper clips. How do I phrase that in this setting?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

So this is an interesting question. You could try to have loss functions that care directly about the physical state, but that quickly runs into the same problems that you were trying to solve. Then you end up again requiring some bridge rules as part of your hypothesis, because the things you care about are not the quarks, the things you care about are some complex macroscopic thingys. You end up requiring your hypothesis to have some bridge rules that would explain how to produce these macroscopic thingys, and this creates all the problems you were trying to avoid. The radical answer that physicalist agents have, or this kind of purist physicalist agents, they say “No. We are just going to be computationalist. We do not care directly about physical thingys, we only care about computations”.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

If you want to be a physicalist paperclip maximizer, then what you need to do in this case is have some model of physics in which it’s possible to define a notion of paperclips and say, the computations that I care about are the computations comprising this model of physics. If there’s a computation that’s simulating a physical universe that has a lot of paperclips in it, that’s the computation that you want to be running. That’s what it means to be a paperclip maximizer if you’re a physicalist.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay, cool. And what would it look like to have a selfish loss function where I want to be a certain way or I want to be happy?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

If you’re doing a selfish loss function, then the computations you are looking at are your own source code. We had this thing before, which we used to define those counterfactuals, which is you know your own source code. So you’re checking whether the universe is running your source code with particular inputs. And that’s also something that you can use to build your loss function. You can say your loss function is that, I want the universe to run the source code which is me, with an input that says I’m taking a nice bath and eating some really tasty food.

**Daniel Filan:**

And pro-social loss functions would be something like me having a loss function that says, “I want there to be lots of programs that simulate various people, what they would do if they were in a nice bath and eating tasty food”. Is that roughly right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

You can think of programs which represent other people, or you can think about something like a program which represents society as a whole. You can think of society also as a certain computation where you have different people and you have the interactions between those people. All of this thing is some kind of a computation which is going on. So, I want the universe to be running this kind of computation with some particular thingys which make me like this kind of society, rather than the other kind of society.

**Daniel Filan:**

Another question I have is, one preference that it seems you might want to express is: if physics is this way, I want this type of thing; but if physics works some different way then I don’t want that anymore. You could imagine thinking, if classical physics exists then I really care about there being certain types of particles in certain arrangements. But if quantum physics exists, then I realize that I don’t actually care about those. I only cared about them because I thought they were made out of particles. Maybe in the classical universe, I cared about particles comprising the shapes of chairs, but in the quantum universe I want there to be sofas. I don’t want there to be chairs because sofas fit the quantum universe better. Can I have preferences like that?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

In some sense you cannot. If you’re going with infra-Bayesian physicalism you’re committing to computationalism. So committing to computationalism means that there is no difference between a thing and a simulation of the thing. So [this](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Treachery_of_Images#/media/File:MagrittePipe.jpg) is actually a pipe. If there’s some type of physical thing that you really want to exist, or someone is just running a simulation of this physical thing, from your perspective, that’s equally valuable. This is an interesting philosophical thing which you can find objectionable, or on the contrary you can find it kind of liberating in the sense that it absolves you from all the philosophical conundrums that come up with, what is even the difference between something running in a simulation and not in a simulation.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Maybe we are all a simulation that’s running inside quantum strings in some sense, but does it mean that we are not real? Does it really matter whether the universe is made of strings or quarks on a fundamental level, or something else? Should it change the extent to which I like trees and happy people, or whatever the thing I like is? If you’re a computationalist you say “I don’t care what’s the basic substrate of the universe. I just care about the computation.”

**Daniel Filan:**

It seems weird because it seems even hard to distinguish - I might have thought that I could distinguish, here’s one universe that actually runs on quantum mechanics, but it simulates a classical mechanical universe. That’s world A. In world B, it actually runs on classical mechanics, but there’s a classical computer that simulates the quantum world. It seems like in infra-Bayesian physicalism, my loss function can’t really distinguish world A from world B. Is that right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

That’s about right. So, you care about which computations are running, or what outputs they have, but you don’t care about the physical implementation of these computations at all.

### Decision theory

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. So to wrap that up: together, we have these world models and we have these loss functions. Can you just reiterate how you make decisions given these world models and these loss functions?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

The way you make decisions is by applying counterfactuals corresponding to different policies. You’re considering, what if I follow this policy, what if I follow that policy, and now you’re supposed to somehow compute what your expected loss is going to be and choose the policy which has the minimal expected loss. The way you actually do it, is you construct counterfactuals corresponding to different policies and the way you construct those counterfactuals is - well, to first approximation they’re just the same kind of logical or computational counterfactual we had before. They’re just saying, suppose that the computation which is me, is producing outputs, which are consistent with this policy, and let’s apply this counterfactual the way we always do it to our hypothesis or prior, and let’s evaluate the expected loss from that. But the thing that you actually need to do is slightly more tricky than that.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

If you do this naïvely, then you run into problems where you are never going to be able to learn. You’re never going to be able to have good learning-theoretic guarantees. Because the problem with this is that if you’re doing things this way, then it means that you cannot rely on your memory to be true. You wake up with certain memories but you don’t know whether those memories are things that actually happened, or maybe someone just simulates you already having this memory. Because you don’t know whether those things actually happened, you cannot really update on them and you cannot really learn anything with certainty. But we can fix this by changing our definition of counterfactuals.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

The way we change the definition is - informally, what it means is, I don’t take responsibility about the output of my own computation if it’s not continuous. If there is some continuous sequence of memories which is leading to a certain mental state, I then take responsibility of what I’m going to do in this mental state. But if something is discontinuous, if someone is just simulating me waking up with some weird memories, then I don’t take responsibility for what that weird simulation is going to do. I don’t use that in my loss calculus at all. I just consider this as something external and not under my control.

**Daniel Filan:**

Formally, what does that definition look like?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

More formally, what happens is to each policy that you correspond some subset of 2^Gamma times Gamma, the subset of things which are consistent with this policy. In the naïve version that would be, let’s look at the computational universe Gamma and let’s look at the source code which is me and see that it outputs something consistent with the policy. In the more sophisticated version we’re saying, let’s also look at 2^Gamma and see with which inputs the universe is actually running me. Then we’re only going to apply our constraints to those inputs which have a continuous history. That’s one thing we need to do, and the other thing we need to do is related to this envelope. We haven’t really discussed it before, but there’s an important part where you’re doing this kind of Turing reinforcement learning thing.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

Your agent has some external computer that it can use to do computational experiments, run all sorts of programs and see what happens. And there, you also need a corresponding guarantee that your computer is actually working correctly, right? Because if your computer has bugs and it’s just returning wrong things, then you cannot really update on seeing what it returns. It creates, again, problems with learning. And in order to not have that, you need to apply a similar fix, where you only apply the constraint of ‘your source code’s outputs are consistent with the policy’ on branches of the history in which you have only seen the computer saying true things.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. I can sort of see how you would operationalize that you only see the computer saying true things, but what does it look like to operationalize that there’s this continuous history of your program existing? If I go to sleep or go under general anesthesia, is that going to invalidate this condition?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

That depends on your underlying model. In our formalism, the inputs to our source code, to our agent, are just sequences of actions and observations. If you go to sleep with some sequence of actions and observations and you wake up and the actions and observations continue from the same point - the things in between, they’re just not contributing to the sequence - that’s continuous as far as you’re concerned. The continuity is not physical continuity, but it’s more like logical continuity. Continuity means that someone runs your code with a certain observation, the action that you output on that observation - that’s also important by the way. Another type of thing, which is not allowed, is someone running you on memories of you doing something which you wouldn’t actually do. That’s also something which we exclude. So then we have observation, action leading from this observation, and another observation. And then you have a sequence of three observations, five, seven, and so on. Those form a continuous sequence. This is continuity. If you have some sequence on which someone is running you, but there is some prefix of the sequence on which the universe is not running you, then that’s considered not continuous.

**Daniel Filan:**

The point of this was so that you could prove loss bounds or something on agents. What loss bounds are you actually able to get in this setting?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

We haven’t actually proved any loss bounds in this article, but the ideas show that you can prove at least some very simplistic loss bounds along the lines of: Let’s assume there is some experiment you can do, which can tell you in which universe you are, or some experiment which you can do, which can at least distinguish between some classes of universes in which you might be. And let’s further assume that this experiment in itself doesn’t carry any loss or almost any loss. Just committing to this experiment doesn’t cost you anything. Then, in this situation, the loss the agent will get would be as if it already knows in which universe or in which class of universes it exists from the start. Or a similar thing, which you can do with computational thingys is, assume that you can run some computation on your computer and the fact of running it in itself doesn’t cost you anything. Then you can get a loss bound, which corresponds to already knowing the result of this computation.

**Daniel Filan:**

That actually relates to another question that I wanted to ask, which is if you imagine implementing an agent in the infra-Bayesian setting, how tractably can you actually compute the outputs of this agent? Or is this going to be something like [AIXI](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AIXI) where it’s theoretically nice, but you can’t actually ever compute it?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

That’s definitely going to depend on your prior which is the same as with classical reinforcement learning. With classical reinforcement learning, if your prior is the Solomonoff prior, you get AIXI, which is uncomputable, but if your prior is something else, then you get something computable. You can take your prior to be some kind of a bounded Solomonoff prior, and then the result is computable, but still very, very expensive. Or, you can take your prior to be something really simple, like all MDPs with some number of states. And then the result is just computable in polynomial time in the number of states, or whatever. So the same kind of game is going on with infra-Bayesianism, depending on what prior you come up with, the computational complexity of computing the optimal policy or an approximately optimal policy is going to be different.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

We don’t have a super detailed theory which already tells us what is happening in every case, but even in classical reinforcement learning without infra-Bayesianism we have large gaps in our knowledge of which exact priors are efficiently computable in this sense. Not to mention the infra-Bayesian case. I have some extremely preliminary results where you can do things like have infra-Bayesian versions of Markov decision processes and under some assumptions you can have policies which seem to be about as hard to compute as in the classical case. There is actually [some paper](https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.15020) which is not by me, which just talks about zero-sum games, reinforcement learning where you’re playing a zero-sum game, but actually can be shown to be equivalent to a certain infra-Bayesian thingy. They prove some kind of regret bound with - I think an efficient algorithm? I’m actually not 100% sure, but I think they have a computationally efficient algorithm. So at least in some cases you can have a computationally efficient algorithm for this but the general question is very much open.

Follow-up research

------------------

### Infra-Bayesian physicalist quantum mechanics

**Daniel Filan:**

Getting more to questions about extensions and follow-ups, what follow-up work to either infra-Bayesianism in general or infra-Bayesian physicalism in particular are you most excited about?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

There’s a lot of interesting directions that I want to pursue with this work at some point. One direction which is really interesting is solving the interpretation of quantum mechanics. Quantum mechanics, you can say, why do we even care about this? Who cares about quantum mechanics, AI is going to kill us all! So I think that it’s interesting in the sense that it’s a very interesting test case. The fact that we’re so confused on the philosophical level about quantum mechanics seems to be an indication of our insufficiently good understanding of metaphysics or epistemology or whatever, and it seems to be pretty related to this question of naturalized induction, which we have been talking about.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

So if Infra-Bayesian physicalism is a good solution to naturalized induction, then we should expect it to produce a good solution to all the confusion of quantum mechanics. And here I have some fascinating, but very preliminary work, which shows that - I think it can solve the confusion. Specifically, I have some concrete mathematical way in which I can build the infra-Bayesian hypothesis that corresponds to quantum mechanics. And I think that I can prove… Well, I kind of sketched it. I haven’t really written out enough detail to be completely confident, except for some simple, special cases. But I believe that I can prove that with this construction, the bridge transform reproduces all the normal predictions of quantum mechanics.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

So if I’m right about this, then it means that I actually know what quantum mechanics is. I have a completely physicalist description of quantum mechanics. All these questions about what actually exists - does the wave function exist? Is the wave function only a description of subjective knowledge? What’s going to happen if you are doing a Schrödinger cat experiment on yourself? All of those questions are questions that I can answer now.

**Daniel Filan:**

Okay. And what does that look like?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

So the way it looks like is basically that - well, in quantum mechanics, we have different observables and usually you cannot measure different observables simultaneously, unless they correspond to commuting operators. So what happens here is, the universe has some Hilbert space and it has some wave function, which is some state - pure, mixed, doesn’t matter - state on this Hilbert space. And then you have all the observables. And the universe is measuring all of them, actually. The universe is measuring all of them and the probability distribution over the outcomes of each observable separately is just given by the Born rule. But the joint distribution - and here is the funny thing, in the joint distribution, we just have complete Knightian uncertainty about what the correlations are. So we’re just imposing the Born rule for every observable separately, but we’re not imposing anything at all about their correlations.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

And I’m claiming that this thing produces the usual predictions of quantum mechanics. And one way to think about it is, when you’re doing the bridge transform, and then you’re kind of doing this infra-Bayesian decision theory on what results, you’re looking at the worst case. And the worst case is when the minimal number of computation is running because of this monotonicity principle. So in some sense, what happens with quantum mechanics is, the decision-relevant joint distribution over all observables is the joint distribution which corresponds to making the minimal number of computations. It’s as if the universe is really lazy and it wants to run as little computations as possible while having the correct marginal distributions and that’s what results. So the interesting thing about this is, you don’t have any - there’s no multiverse here. Every observable gets a particular value. That’s just, you have some randomness, but it’s just normal randomness.

**Vanessa Kosoy:**

It’s not like some weird multiverse thing. There’s just only one universe. You can get some weird things if you are doing some weird experiment on yourself where you are becoming a Schrödinger cat and doing some weird stuff like that, you can get a situation where multiple copies of you exist. But if you’re not doing anything like that, you’re just one branch, one copy of everything. And yeah, that’s what it looks like.

**Daniel Filan:**

Sure. And does that end up - so in quantum mechanics, there’s [this theoretical result](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell%27s_theorem) that says, as long as experiments have single outcomes and as long as they’re probabilistic in the way quantum mechanics says they are, you can’t have what’s called local realism, which is some sort of underlying true fact of the matter about what’s going on that also basically obeys the laws of locality, that also doesn’t internally do some faster-than-light or backwards in time signaling. And there are various parts of that you can give up, you can say, “Okay, well it’s just fine to not be local.” Or you can say, “Experiments have multiple results” or “there’s no underlying state” or something. It sounds like in this interpretation you’re giving up locality, is that right?

**Vanessa Kosoy:**